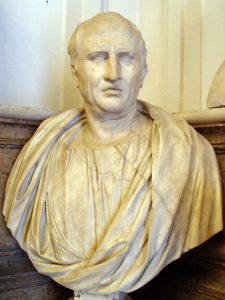

Cicero on Living a Stoic Life

By John Sellars

What is involved in living a Stoic life? In his book On Duties (1.107 ff.) the Roman statesman and philosopher Cicero outlines a theory involving four distinct rules for living a life. This is known as the four personae theory and it is usually supposed that Cicero is following a now lost work by the Stoic philosopher Panaetius. There are scholarly debates about how closely Cicero follows Panaetius and to what extent Panaetius might be deviating from the orthodox Stoic view, but putting those questions to one side Cicero’s account is on its own terms an interesting window on what might be involved in living a Stoic life.

We have, Cicero says, two natures, one common and one individual. Our common nature as human beings offers one sort of guide to how to live. The fact that we are rational, social animals gives us one set of pointers to what a life in accordance with nature might look like. However we also each have our own individual natures, the specific set of character traits that we have not chosen and that make us who we are. Some people are loud and outgoing; others shy. Some are sporty and physical; others intellectual and bookish. Some are artistic by nature; others more inclined to technical problems. None of us chose the particular set of strengths and weaknesses that we have; they have been given to us by nature.

Central to Cicero’s account is the claim that a life in harmony with nature ought to be sensitive to these aspects of our individual nature. It is not simply a question of following universal guidelines about being rational or virtuous; it is also about being sensitive to who we are as individuals. There is of course the possibility that the two might come into conflict with one another, in which case Cicero says that universal nature comes first: ‘Each person should hold on to what is his as far as it is not vicious … we must act in such a way that we attempt nothing contrary to universal nature; but while conserving that, let us follow our own nature’.

So, while our primary commitment ought to be to universal nature, we ought also to be true to ourselves, our unique individual natures. Living in harmony with nature is as much about living in harmony with our own nature as it is conforming to Nature with a capital ‘N’. Of course this shouldn’t be much of a surprise given that the former is merely a local expression of the latter.

What we need, then, is plenty of self-knowledge about who we are, what our strengths and weaknesses are, and enough self-belief to remain true to what we find rather than trying to be like other people: ‘everyone ought to weigh the characteristics that are his own, and to regulate them, not wanting to see how someone else’s might become him; for what is most seemly for a man is the thing that is most his own. Everyone, therefore, should acquire knowledge of his own talents, and show himself a sharp judge of his own good qualities and faults’.

So far I’ve mentioned just two elements and at the outset I said there were four. The other two, which Cicero introduces later, are chance or circumstance and our own pursuits. Chance or circumstance refers to the aspects of situations that are out of our control. Someone might be a naturally gifted opera singer but find themselves at home with small children unable to realize that talent. Others might by nature be gifted sportsmen but due to injury be unable to compete any more. Chance can throw up situations in which we are unable to remain true to our individual natures, although if one buys the broader Stoic view of fate one would have to accept that these chance situations are also ultimately the product of Nature.

Our own pursuits includes things like the career we choose for ourselves. Cicero says that this is the one of the four elements where we actually have some choice. We decide whether to train as a doctor or a bricklayer. Cicero suggests that this ought to involve significant deliberation. However it is not clear just how much choice there really is, as the sort of deliberation Cicero has in mind ultimately boils down to self-examination so that we can find out who we really are. The person well suited to become a doctor may not be well suited to the life of a bricklayer, and vice versa. As Cicero puts it, ‘in such deliberation all counsel ought to be referred to the individual’s own nature’. But we also need to take into account the chance circumstances in which we find ourselves: ‘Nature carries the greatest weight in such reasoning, and after that fortune’.

So, how to live a Stoic life? The top priority remains a life in harmony with Nature/reason/virtue. Then there are the chance circumstances in which we find ourselves, out of our control and ultimately laid down by Nature too. But also central in Cicero’s account is the idea that we remain true to our own individual natures, to who we are. Thus self-knowledge becomes vital for a life in harmony with nature. Once we feel secure that we know who we are, what our strengths and weaknesses are, where we fit in the world, then the only decision to be made is how best to remain true to ourselves in the circumstances in which we find ourselves.

John Sellars is currently a Research Fellow at King’s College London. His principal area of research is Ancient philosophy, but he is equally interested in its later influence and have wide interests in Medieval, Renaissance, and Early Modern philosophy. He has written two books on Stoic philosophy:Stoicism and The Art of Living. Read more about John’s work on his website, and also see his blog on Stoicism.