I’ve been dying since the age of 8. I’ve died from leprosy, AIDS, brain tumors, cholera, TB, rabies (at least four times), the plague, and many other oft-mortal afflictions I have since forgotten. Amazingly, from all these, I have recovered. Further, I’ve been going blind for years, but still miraculously see—albeit with assistance of pretty strong glasses. I am—or perhaps was—a full-blown hypochondriac.

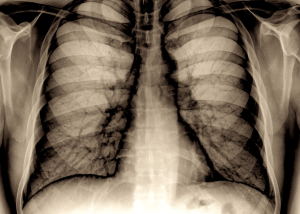

You can imagine, then, when my primary care physician identified a heart murmur (caused by a leaky heart valve) in a regular physical when I was 31—meltdown time. Add in some suspect family history of heart issues, and now I clearly had something medically verifiable to worry about!

And so it went—sometimes better, sometimes worse—for about 15 years, with regular, rather terrifying trips to the cardiologist for an echocardiogram to ensure that the heart valve wasn’t getting worse, necessitating surgery. Until about three years ago, that is, when my uncle introduced me to Stoicism. This ancient Greek and Roman philosophy of life fundamentally reoriented my perspective on my condition in particular and on my life more broadly. It ultimately helped me make it through what I consider the three stages of my health “event”; let’s call them:

- Bad news coming? Prepare for it.

- Open-Heart surgery: Why worry?

- Surgery is done: I made it, right?

Bad news coming? Prepare for it.

I scheduled my regular echocardiogram for 3 pm on Thursday, November 10, 2016. Instead of my usual approach to the echo, trying to pretend it’s not happening, I decided to use Stoic philosophy to prepare. Having immersed myself for the past three years in the thoughts and practices of the ancient Stoics—Epictetus, Seneca, Marcus Aurelius—as well as those of modern interpreters such as Donald Robertson, Ryan Holiday, and Pierre Hadot, this seemed an ideal opportunity to confront my life-long existential fears.

In preparation for the echo appointment and the possible bad news I would receive, I practiced the premeditatio malorum, the anticipation or premeditation of adversity. The Stoic concept here is that anticipating a difficult scenario allows one to better handle it when the scenario or something similar to it occurs. As the Roman Stoic and Statesman Seneca noted: “He robs present ills of their power who has perceived their coming beforehand.” This notion is borne out by research on similar approaches in cognitive behavioral therapy—which itself has origins in Stoic thought (see Donald Robertson’s Stoicism and the Art of Happiness).

Approximately once every other day in the three weeks leading up to the appointment, I would close my eyes on the train ride home from work (don’t try this if you drive to/from work) and engaged in a very specific premeditatio malorum: imagining receiving bad news from the cardiologist. This “imagining” took the form of a 10-15 minute meditation in which I would picture myself arriving at the cardiologist’s office, doing the echocardiogram, talking to the cardiologist, and receiving the news that I would need open heart surgery or that my problem was so severe that it was inoperable. (I know this sounds really uplifting, but bear with me!) While this wasn’t a particularly pleasant imagining, becoming accustomed to the negative news prepared me well for the actual “bad news” event.

Additionally, in the meditation I constantly kept the fundamental Stoic notion in front of my mind: certain things are in our control, and others are not. And Stoics consider those things not in our control to be “indifferent.” In the Stoic view, they should not bear upon our sense of peace and tranquility because we cannot control them. Matters including the body—such as whether my heart is malfunctioning—are clearly beyond my direct control. However, what I can control, through training and practice, is how I react mentally to those things beyond my direct control. As Shakespeare’s Hamlet noted, in a very Stoic phrase, “Nothing is good or bad but thinking makes it so.” Or, as the Stoic teacher Epictetus put it: “It is not things themselves that upset us but our judgements about these things.”

I’m happy to report that, given my preparation, receiving the “news” from the cardiologist that I would need open-heart surgery was nearly an anti-climax. I expected it. Even the candor and bluntness from my cardiologist about my situation was more amusing than disturbing. It was almost like watching a movie I had seen many times before—it had lost its emotional punch.

Open-Heart surgery: Why worry?

After discussing the echocardiogram results with multiple cardiologists—essential due diligence—it was clear that surgery was the best courses of action to repair or replace the leaky valve sooner rather than later. Waiting for it to develop into a geyser was medically inadvisable, shall we say. The good news was that the likelihood of a successful repair or, if needed, replacement of the valve was very high. The bad news was that it was open-heart surgery. As in, they cut you open, stop your heart, cut around in it, restart said stopped heart, and close you back up. For a hypochondriac, even a newly Stoic one, yikes!

I settled upon two approaches to the impending surgery. The first was to embrace the Stoic concept of “hic et nunc”—the here and now. That is, an intense focusing—a mindfulness really—on the immediate moment. The Stoics believed that one of the challenges of humanity is its ability to ruminate on the past and anticipate the future.

As Seneca noted:

Wild beasts run away from dangers when they see them. Once they have escaped, they are free of anxiety. But we are tormented by both the future and the past.

Roman emperor and Stoic Marcus Aurelius admonished himself to

Never let the future disturb you. You will meet it, if you have to, with the same weapons of reason which today arm you against the present.

Instead of getting lost in worry over the future surgery, I did my best to enjoy and live in the moment—appreciating the beauty and wonder of all the things around me, from my own ability to walk, talk, and see, to the company of colleagues, friends, and loved ones. If anything, my ability to do this successfully was amplified by the upcoming surgery as I was able to more easily appreciate the things around me.

At certain times, though, such as during a morning or evening meditation, I did consider the upcoming surgery—after all, Stoicism does ask us to prepare for challenges. We are not to live in ignorance of challenges that will arise, but we are to prepare rationally and within the context of what we can control and not control. What, then, was the Stoic attitude I took toward the upcoming operation? Acceptance—it is what it is. As the Stoic teacher Epictetus exhorted his students: “make the best of what is in our power, and take the rest as it naturally happens.” Once it was clear that surgery was the logical approach, the only thing to do was to accept it as simply necessary. Those things we cannot control we should accept as a natural part of existence.

Ah, but what if I died because of the surgery? While this wasn’t likely, it wasn’t impossible either. Having the operation was a whole lot more dangerous than my average day, after all. The doctors seemed quite confident, but, then again, it wasn’t their heart that was getting stopped, cut up, and restarted. Not only that, but if I didn’t die from surgery, surely I will die at some point (we all do—sorry to be a downer!). As Epictetus noted: “I am not eternal, but a human being; a part of the whole, as an hour is of the day. Like an hour I must come and, like an hour, pass away.” While I cannot claim to have overcome this existential challenge, I was able to wrestle with the issue without too much fear. One approach I took was to appreciate that there are far worse ways to die than on the operating table—after all, you are out cold and unaware of what is occurring. As I went into surgery early on March 22, this thought provided some comfort.

Surgery is done: I made it, right?

I wake up with a start; I have tubes coming out of everywhere and my arms are strapped down. Breathing tube, chest tube, catheter, etc. My wife is talking to me—nurses, machines, beeping. I motion for something to write on and scrawl something about the breathing tube and when it might come out. My wife says that it’s coming out soon, but the nurse needs a doctor’s approval. I write, “I can take it out—I’m a doctor,” and then I sign it. That makes her laugh: I’m a doctor of education—not an MD—so while I might be able to theorize about an educational problem, I’m not exactly qualified to remove anyone’s breathing tube, never mind my own. Well, at least my sense of humor is intact.

Two main issues arose while recovering in the hospital: First, the loss of independence and control. Second, the fear that something bad was going to happen—some sort of complication. I did better with the first issue than the second, but Stoicism was helpful for both.

Being in recovery from major surgery means a radical loss of control of bodily things. You can’t even go to the bathroom on your own. Thankfully, Stoicism is perfectly aligned for this sort of challenge. As already mentioned, Stoics view things outside the mind as fundamentally not in our (full) control. This applies to all the things that happen to us—those things in the hands of Fortune—as well as the bodily matters over which we exercise only partial control. This acceptance of loss of control is an essential way to remain content and tranquil when in what otherwise would be a frustrating situation. Epictetus exhorted his students as follows:

Being educated [in stoic philosophy] is precisely learning to will each thing just as it happens.

The Stoics often advocated going beyond acceptance of external events. One should embrace the situation as you find it thrust upon you, for it exists as it is at the instant it is occurring and so it cannot be otherwise. As Seneca said:

A good person dyes events with his own color… and turns whatever happens to his own benefit.

How, then, to turn this event to my own benefit? The flip side of your lack of bodily autonomy after surgery is your dependence on others—in particular, the nurses, technicians, and other health care professionals whose job it is to help you get better. In these exceptional human beings a wonderful Stoic opportunity presents itself. Stoicism, in contrast with the stereotype of a “stoic” person, encourages us to engage fully with other people, for they share a spark of the divine in their ability to reason. As our brothers and sisters, according to Marcus Aurelius:

We were born to work together like feet, hands, and eyes, like the two rows of teeth, upper and lower.

Seneca notes of Stoicism that

No school has more goodness and gentleness; none has more love for human beings, nor more attention to the common good.

I’m naturally an outgoing person, very engaged with those I meet. But I made a special effort to be so in the hospital—as much as possible treating each person as an individual, thanking them for the work they do, and being upbeat and optimistic about whatever somewhat unpleasant thing they needed to do to me next—poking me with needles, waking me up at 3 am to take my blood pressure, making me eat hospital food. The good cheer I gave out was returned to me many, many times over, not only by the staff but simply by my own actions. As Marcus Aurelius asked:

How then can you grow tired of helping others when by doing so you help yourself?

The most difficult part of recovery was the implicit existential threat—amplified by the incessant beeping of the monitors to which I was connected. Two days after surgery, I developed atrial fibrillation (“AFib”), which is the heart beating rapidly and out of sync—mine was moving at 130 beats per minute. AFib is common enough after open-heart surgery, but that didn’t make it any less scary. To deal with this unexpected challenge, I returned to Stoic meditations, in particular, one known as the “view from above.”

This meditation involves imagining yourself leaving your body and floating up above it, slowly moving up to a perspective far above the earth. In doing this, you picture yourself surveying all around you and seeing how small you are in the broader scheme of existence—just one soul and one life among billions, all inhabiting a planet that, from a distance, looks to be just a “pale blue dot” in the words of astronomer Carl Sagan. This meditation helped me put my life in perspective, as only one among many, part of a broader whole. True, it, too, will end; if not now, then in 10, 20, or 30 years. Acceptance of this fact can help one live a fuller life, while we have one to live. Contemporary Stoic author Ryan Holiday notes, “Reminding ourselves each day that we will die helps us treat our time as a gift.”

I’m happy to report that I’m home now as I write this, with surgery three weeks in the past, feeling quite well. AFib is now under control, thanks to a well-calibrated “Zap!” from a defibrillator last week. My wife says my heart has got the beat now, thankfully! I am extraordinarily thankful to all those who helped me get through this—from an incredibly skillful surgeon, caring and talented doctors, nurses, and other health care workers to loving and supportive family, friends, and co-workers. I am also thankful for an ancient philosophy called Stoicism, which is as powerful at addressing the human condition today as it was in Ancient Greece and Rome.

Would I still consider myself a hypochondriac? Perhaps at times, but one far better equipped to deal with life’s challenges. I have found that this experience, and my reaction to it in a Stoic context, has changed my perspective on life in a fundamental way, undermining the fear at the root of hypochondria. I am hopeful that this article can help others discover ways to overcome their personal challenges—both real and imagined!

Dr. Alexander Ott is associate dean of academic affairs at Bronx Community College of the City University of New York. He holds an undergraduate degree in philosophy from SUNY Geneseo and a master of arts and doctor of education degrees from Fordham University. Dr. Ott has been studying and practicing Stoicism for three years.

I was looking for a long time for such an example.

Thank you for sharing your story!

Hi Valeri:

Glad to hear this was helpful.

All the best,

Alex

Nicely done, Dr. Ott! As a physician, I particularly appreciate the anxiety of dealing with a potentially serious operation. It seems your Stoic values and teachings have served you well!

Best regards,

Ron Pies

Ronald W. Pies MD

Hi Ron:

Many thanks! I wonder if there is much research on helping patients deal with the anxiety of surgery. I couldn’t find much in my search, but I’m not a Dr. (MD, that is :)), so I might not be looking in the right places. Do you know, by any chance?

It seems to me that Stoicism offers one way to approach elective (yet serious) surgery that could be very helpful for some people. Of course, most people aren’t practicing Stoicism before they learn of the need to have surgery, so any “Stoic intervention” would have to be a quick version, and I don’t know how viable that would be…

Alex

Thank you so much for telling your story and how you put Stoic theory into practice. I found it very uplifting.

And let’s hope, fate permitting, you continue to make a full recovery.

Hi Tony-

Thanks for the good wishes and the kind words–recovery is going well. It’s interesting–I actually think the experience was a net positive at this point. I would prefer not to do it again, but still…

Alex

Hi Alexander

I was born with A

Ostium primum asd

Cleft tricuspid valve

I went into complete heart block 29.4.88 at age ten. I had open heart surgery and a pacemaker (one of many) I think it’s easier for kids as I have never worried about it till I got misinformation as an adult about my heart (which is fine) when it was actually my Pacemaker wires playing up due to a loose connection! The wires are 30 years old now so they are going to give up eventually – despite that. Each surgeon realised it’s not an easy task to replace them in the same spot.

I also have dual cochlear implant due to hearing loss at birth and profound deafness around the age of 13.

Your the first person I have come across with congenital complex heart and another Dural sensory disability who is close to my age group .

Best wishes in your recovery

Zoe

Hi Zoe:

Thanks for sharing your story. Your distinction between how children view the world compared to adults is an important one, I think. We could learn much from children under age ten, I think. They are often centered in the moment and have a sense of wonder at the things around them. Losing these two characteristics seems to be typical as we get older–but with the right training of the mind, they can be recaptured, at least to some extent.

Best wishes to you as well,

Alex

Hi, Alex…Great questions! There is a literature on reducing anxiety prior to surgery, but I don’t know of any studies looking at the use of elements of Stoicism. I suspect that, for most people facing surgery, the most important element of reassurance is a good, trusting relationship with the surgeon–which is not always easy and sometimes very hard, indeed (some surgeons are more willing than others to get to know the patient, prior to surgery). There are of course studies of hypnotherapy and “music therapy” [see references below], and one article provides a good review of these modalities [see https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0072741/%5D. I think people will differ widely on how helpful they would find philosophical approaches to anxiety–but most will probably be unprepared for the rigor of Stoic teachings in the acute surgical setting. I hope these references are helpful. Take care and be well,

Ron

References

Hizli et al, Int Urol Nephrol. 2015 Nov;47(11):1773-7.) [pre-surgery hypnosis]

Chang et al, Urol Int. 2015;94(3):337-41). [music prior to surgery]

Very helpful, Ron. Thank you!