Stoics have been known to connect inner tranquility with peace and tranquility in relations with others. This may be why many Stoics have sought peace in the external world as well as the internal. From Seneca vainly pleading with Nero to practice clemency and moderation, to Musonius Rufus vainly stepping into mutually-hostile groups of Roman soldiers and attempting to talk them out of fighting, Stoics have a history of trying to preach peace – and of being disregarded.

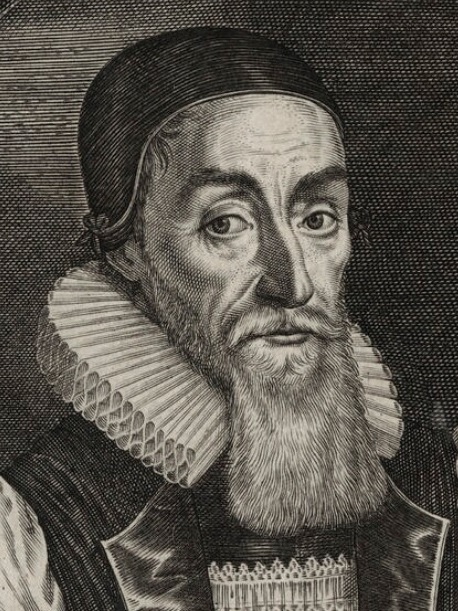

Into this tradition of preaching both internal and external peace falls Joseph Hall (1574-1656), an Anglican clergyman who tried to stand between hostile English religious forces whose antagonisms, despite Hall’s pleas, ultimately contributed to the English Civil War. Though his peaceful counsels were disregarded on the national level, his bestselling work Heaven Upon Earth appealed to readers who at least sought inner tranquility.

Hall was part of a Renaissance/Early Modern movement known as Neo-Stoicism. While the Christian world had never fully forgotten or ignored the Stoics, the appearance of new printed editions of many Stoic classics during the Renaissance – and the discrediting of spurious Stoic works – as well as commentaries such as those of Justus Lipsius, prompted a renewed interest in applying at least some Stoic insights to Christian living, especially as an era of religio-political uncertainty, strife and outright war.

Joseph Hall, a very English Stoic, was born near a town with the very English name of Ashby-de-la Zouch. As he grew up, inspired by a pious mother, he took an interest in religion. He wanted to be a Church of England priest, which generally required a course of instruction in one of the great English universities. Hall’s father – Hall had many siblings – wasn’t sure he could afford university for him, and was originally going to indenture him to receive private, non-university tutoring. At the last minute, Hall’s father changed his mind, and soon afterward a relative agreed to pay much of Hall’s expenses at Cambridge’s Emmanuel College.

Hall later described his many years at Emanuel as the best years of his life. Emmanuel was known as a center of Calvinism whose graduates went on to become influential Calvinist ministers and bishops in the government-established Church of England. Trained in good Calvinist doctrine while studying classic works like those of Seneca, Hall developed into a learned young man.

Hall also showed a literary bent, becoming known for his poetry. He may have helped write a play performed by students at another Cambridge college (Emmanuel would presumably have frowned on theatrical productions). The last of a trilogy, the play was a comedy with a serious undertone – following Cambridge graduates as they went about the country in a frantic search for decent-paying jobs.

Hall also published satirical verses taking caustic aim at social abuses, such as greedy doctors and lawyers, and hitting the government even closer to home by denouncing the enclosure of agricultural land by rich farmers at the expense of poor agriculturalists. High-up Church officials put a collection of Hall’s satires on a list of books to be burned, but somehow the ecclesiastics promptly changed their minds and gave the work a reprieve.

As Hall moved into a clerical career, he continued writing, but his focus turned from direct social satire to preaching godliness. Clerical appointments were in control of influential laymen, and one of these, Sir Robert Drury, arranged to make Hall the parish priest at Hawstead, where his position turned out to be ill-paid. As Hall later noted, in order to earn enough money to buy books, he had to write books of his own. He was also harassed by one of Drury’s friends, a “bold and witty atheist” named Lilly. As Hall recalls it, in his daily prayers he asked God to “remove” Lilly “by some means or other,” and indeed Lilly later died of a “pestilence” – supposedly while on the way to London to lobby against Hall.

Another consolation was that Hall got married (as Anglican priests are allowed to do). The couple had many children, and later, by Hall’s account, a “great man” observed his numerous offspring and said that children made a rich man poor. “Nay, my Lord,” Hall claims to have replied, “these are they, that make a poor man rich; for there is not one of these, whom we would part with for all your wealth.”

In 1606, while at Hawstead, Hall published Heaven Upon Earth, a Neo-Stoic work which would prove very popular, going through eight editions (four stand-alone editions, and four more editions in which Heaven Upon Earth was combined with some of Hall’s other works). Hall’s goal, he told the reader, was “to teach men how to be happy in this life.” Here, Hall declared, he had “followed Seneca; and gone beyond him: followed him, as a philosopher; gone beyond him, as a Christian, as a divine.”

Hall wrote that be both envied the Stoics – envied, because they had come up with “such plausible refuges for doubting and troubled minds;” pitied, because without the benefit of the Christian revelation, Stoic methods would only lead to “unquietness.” No “heathen” ever “wrote more divinely” than Seneca, and “never any philosopher (wrote) more probably.” Hall would be a Stoic if “I needed no better mistress than nature” – i. e., philosophy without Christianity. But to obtain true tranquility in this life required Christianity, not just philosophy: “Not Athens must teach this lesson, but Jerusalem.” Key Stoic ideas, however, could help guide the Christian.

Heaven Upon Earth proceeded to list the reasons men lacked spiritual peace, and proposed remedies taken from both Calvinist Christianity and Stoicism.

(T)ranquility of mind…is such an even disposition of the heart, wherein the scales of the mind neither rise up towards the beam, through their own lightness, or the overweening opinion of prosperity, nor are too much depressed with any load of sorrow; but hanging equal and unmoved betwixt both, give a man liberty in all occurrences to enjoy himself.

Hall listed the various threats to mental tranquility. He began with sin. A person guilty of sin could not attain tranquility in this life, or the next, unless he repented and turned to Christ, whose sacrifice on the cross repaid the infinite debt which sinful humans owed to God.

In addition to sin, men had their tranquility threatened by “crosses,” or “sense or fear of evil suffered.” Millions of people lived in “perpetual discontentment” due to crosses such as severe illness or excessive grief. For these and other crosses, Hall’s advice was: “make thyself none; escape some; bear the rest; sweeten all.”

Heaven Upon Earth proposed a distinctly Stoic remedy for fears of future misfortune such as sickness, poverty, and imprisonment: “present to ourselves imaginary crosses, and manage them in our mind before God sends them in event.” In this way, “while the mind pleaseth itself in thinking, ‘Yet I am not thus,’ it prepareth itself against (the possibility that) it may be so.”

Like Stoics, Calvinists believed in a strict divine necessity, such that whatever happened, had to happen. Calvin himself had frequently been obliged to fend off accusations of Stoicism, arguing that his ideas were not Stoic. Calvin’s ideas of predestination were based on a sovereign God outside the universe making decrees for the universe, while the Stoics put God in the universe. Still, the similarities were there, and Hall reflected these ideas of metaphysical necessity with the comforting advice that crosses are part of the divine plan.

“Crosses, unjustly termed evils, as they are sent of him that is all goodness, so they are sent for good, and his end cannot be frustrate(d).” Like a doctor prescribing cures for physical ailments, God prescribed certain crosses as cures for spiritual ailments: pride, laziness, anger and other sins. “The loss of wealth, friends, health, is sometimes gain to us. Thy body, thy estate is worse: thy soul is better; why complainest thou?” God knows the best mix of good and bad fortune to suit any particular person’s condition.

The fear of death was another cross. To Hall, such fear could involve shrinking from the painful process of dying, or fear of what happens after death. The true Christian, having laid his sins at the foot of the cross, need not fear – “the resolved Christian dares, and would die, because he knows he shall be happy” in Heaven.

Like Marcus Aurelius, Hall dismissed the spurious immortality of fame – “the fame that survives the soul is bootless,” i. e. useless. Letting one’s tranquility be disturbed by the bad opinions of enemies is also useless and harmful. Denouncing the desire for popularity, Hall apostrophized: “O fickle good, that is ever in the keeping of others! especially of the unstable vulgar, that beast of many heads; whose divided tongues, as they never agree with each other, so seldom…agree long with themselves,” if they agree at all.

In reality, earthly pleasures were insecure and fleeting, giving in any case no contentment because they were insatiable and had no logical stopping point. Prosperous people were more “exposed to evil” than the poor, who having little to lose could more easily rebuilt after a disaster. The enjoyment of “pleasure” or “sensuality” could turn men into animals (invoking the myth of Circe). And pleasure could depart rapidly, without notice.

Anyone undergoing crosses could turn to divine contemplation: “He that will have and hold right tranquillity, must find in himself a sweet fruition of God, and feeling apprehension of his presence.” As long as Hall knows “that God favours me; then I have liberty in prison, home in banishment, honour in contempt, in losses wealth, health in infirmity, life in death, and in all these, happiness.” Daily communion with God, giving Him thanksgiving and prayers, would keep the reader in touch with the source of all tranquility.

Hall also advised the reader not to take action before satisfying all conscientious doubts as to the action’s rightness. Hall gave the example of lending at interest (“usury”). Hall thought he would not be secure in his conscience unless he refrained from offering such loans, despite the plausible-seeming arguments in favor of moderate interest. It’s hard “to determine, whether it be worse to do a lawful act with doubting, or an evil with resolution.” Acting in doubtful cases would unsettle the conscience, threatening tranquility. Hall would come to observe too many situations where – at least to his way of thinking – people rushed into conflict without first fully weighing the issues at hand in the tribunal of conscience to decide if action was warranted.

In addition to Heaven Upon Earth, Hall wrote many other devotional books, including meditations upon God’s work in nature – even watching a spider could be a prompt for deep spiritual reflections. Gathering fame as an author, Hall began improving his earthly fortunes, switching patrons from Robert Drury to Edward Denny (a future Earl of Norwich). Through Denny’s influence, Hall obtained a new parish in Waltham, Denny’s home base on the east coast of England. The pay was better than at Hawstead, but Hall denied to his old patron Drury that his switch was purely mercenary in motive. True, Hall’s discontent with his position at Hawstead had started with the financial situation, yet his ultimate decision for Waltham was based on the greater spiritual harvest to be gathered there.

Hall was also invited to London to preach to Prince Henry, elder son of King James I, and was invited to become one of Henry’s twenty-four chaplains, visiting Prince Henry one month per year to share his duties with a co-chaplain. This brought Hall into the lively mini-court of the heir to the throne. Like Hall, Prince Henry was a pious Calvinist. The Prince surrounded himself with ambitious literary and practical men. Henry had a particular desire to lead the Protestant forces of Europe in what we now know as the lead-up to the Thirty Years’ War.

Professor Geoffrey Aggeler suggests that the English Neo-Stoics tended to be Calvinists. Certainly, the circle around Prince Henry included such Calvinist Neo-Stoics. King James noticed this, and warned his son against “Stoicke insensible stupidity.” To Prince Henry and many of his associates, Neo-Stoicism was a fighter’s faith by which one prepared for life as a self-disciplined Protestant soldier or statesman. The Prince never had the chance to be the chevalier of Protestantism, dying of an unexpected illness in 1612 at the age of 18. Many of the Neo-Stoic Calvinists in Prince Henry’s circle would drift away from the monarchy, and toward Parliament, as their preferred instrument for making England more Godly.

But not Hall. King James selected the now prominent and respected cleric for important religious negotiations. In 1617, when James went to Scotland (where he ruled as James VI), he wanted the famously-Calvinistic Scottish church leaders to adopt certain practices, such as kneeling at Communion, which Scottish Calvinists considered “papist.” On James’ instructions, Hall, who was in the king’s entourage, tried to persuade the suspicious Scottish churchmen that these matters of ritual could be accepted because they were adiaphora – matters of indifference (the same term the old Stoics had used for indifferent matters like health and reputation, though in this context Hall meant indifferent from the standpoint of salvation). Hall had more credibility with Calvinists than many other Church of England figures – which is why James used him as an emissary – but Scotland was not religiously pacified.

James also sent Hall as one of the English delegates to the Dutch city of Dordrecht (Dort) to address a dispute roiling the Protestant world. A minister named Arminius defended the doctrine of free will in a challenge to Calvinist doctrines of predestination and election. The 1618-19 Synod of Dort upheld the Calvinist position, which Hall supported. However, Hall perceived a tendency on the part of the disputing parties to fight with stubbornness and acrimony on debatable points, which he warned against in a speech to the Synod. He called for (Protestant) unity amidst the various factions of the time: “We are brothers, Christians, not Remonstrants, Contra-Remonstrants, Calvinists, or Arminians.” Hall was soon obliged to return to England for reasons of health. He expressed his frustration at existing religious animosities in an unpublished writing called Via Media (the middle way): “I see every man ready to rank himself unto a side. I see no man thrusting himself between them, and either holding or joining their hands for peace. This good, however thankless, office, I have here boldly undertaken.” Hall was quite willing to sacrifice religious freedom for the sake of religious peace, supporting government censorship of fruitless religious debate.

In 1625, King James died. So long as the church had bishops and a sufficiently-formal liturgy, James had been quite willing to allow Calvinism among the clergy. Had Prince Henry survived, this situation might have persisted – if Hall were non-Stoic enough to feel regret for the past, he might have wished Henry had lived to inherit the crown and keep unity among English Protestants. Instead, the crown was inherited by Henry’s younger brother Charles, whom Henry has joked would make a better Archbishop of Canterbury than a king. Sadly, even this snide put-down had been too optimistic.

One of Charles I’s early actions was to make Joseph Hall the Bishop of Exeter, in England’s southwest. But this appointment was made in 1627, during an early, moderate phase of Charles’ reign. It was not long before Charles decided upon a church policy different from Hall’s – a policy advocated by men like William Laud, soon to be Archbishop of Canterbury. Laud and his faction rejected Calvinism completely, embracing the “Arminian” doctrines the Calvinists detested. The English Church was to be forced to accept free will whether it wanted to or not. Anglican clergy were also pressured to emphasize high-church ritual rather than preaching – unless the preaching was to Laud’s liking.

As bishop of Exeter, Hall strove to improve the number and quality of preachers of the Gospel in his diocese. He did not monitor his Calvinist clergy for strict liturgical compliance – many of these clergy followed a slimmed-down liturgy focusing on Bible-reading and preaching. Given that the Laudian faction was taking over the Church, Bishop Hall soon faced rumors that he was a Puritan sympathizer. In a memorandum, probably written for circulation among influential persons, Hall defended himself.

He defined Puritanism narrowly as meaning disturbers of the Church’s peace, and denied that Puritans in that sense were in his diocese. He had expelled such disturbers from, or kept them from entering, the diocese. Enforcing the Anglican Church’s legal monopoly on religious worship, Bishop Hall denied the right of anyone – Catholic or Protestant – to worship in a church separate from the Anglican Church. Within the Anglican Church, however, Hall was willing to be tolerant of most people who behaved themselves and maintained religious peace. Going on the offensive in his memorandum, Hall suggested that “Puritan” was a slur which lazy or corrupt clergy and laity employed to denounce people more Godly than themselves. The bishop said he would spend more effort on getting rid of drunken and profane clerics than on monitoring pious ministers for Laudian high-church conformity.

Hall wasn’t simply facing pressure from Laudians who thought he was too Puritan, he also had to deal with fellow-Calvinists who thought he wasn’t Puritan enough. For example, the militant element of the English Puritan faction rejected the office of bishop as an unscriptural relic of papism, advocating instead that the English Church be governed by bodies of elders – “presbyters.” Liturgical formality above the minimum should also be abolished, and special feasts (like Christmas) should also be cast away, according to the militants. To answer such claims, Hall wrote in defense of episcopal government against the advocates of presbyterianism, prompting angry responses from various Puritan pamphleteers, including the poet John Milton.

In 1639, Bishop Hall published a booklet entitled Christian Moderation. Showing the Neo-Stoic connection between personal moderation and moderation in matters affecting the body politic, the bishop started out with a discussion about abating one’s individual passions. From there, without going into specific doctrinal topics, Hall gave recommendations for the proper spirit in which religious discussion ought to be conducted. Bishop Hall rejected certain debating tactics which improperly inflamed the passions but which had become all too common in religious disputation. These included what we would today call straw-manning and guilt by association. Ad hominem attacks, and exaggeration of the differences among the contending parties, also met with Hall’s displeasure. Even if Englishmen couldn’t reach theological agreement, “we should compose our affections to all peace…What if our brains be diverse! yet let our hearts be one.”

When Parliament convened around this time, Bishop Hall attended the House of Lords, of which, like all bishops, he was ex offico a member. The presence of bishops in Parliament was one of the complaints of the radical Puritans in the House of Commons, and as the conflict between King and Parliament grew hotter, the Commons passed bills to kick the bishops out of the Lords. Hall and other bishops eloquently defended their right to be involved in Parliamentary affairs, and the Lords blocked the Commons’ bills. Attempting a new tactic, the Commons impeached Hall and other bishops for governing the Church without Parliamentary consent.

Then as 1641 drew into December, angry London mobs threatened the bishops when they tried to attend Parliament. Hall and several other bishops signed a protest, declaring that until they could take part in Parliamentary deliberations, free from mob intimidation, Parliament’s acts would not be valid. Now the Commons impeached Hall and the other signatories for high treason, and the House of Lords committed them to the Tower of London. Meanwhile, King Charles had appointed Hall as the new bishop of Norwich, near the east coast and about a hundred miles southeast of Hall’s old parish of Waltham. But for now Hall was in a cell and could not visit Norwich. He did have the chance to preach from the Tower to interested London citizens, and he wrote to express relief that the Tower’s walls at least protected him from the mob.

In Heaven Upon Earth, Hall’s words of comfort had included solace for prisoners, and Hall may have had occasion to turn to his own words: “Am I in prison, or in the hell of prisons, in some dark, low, and desolate dungeon?…What walls can keep out that Infinite Spirit that fills all things? What darkness can be, where the God of this sun dwelleth? What sorrow, where he comforteth?”

In mid-1642, after some wrangling between the Houses, Parliament decided to release Hall and the other bishops without resolving the treason charges. Hall had to pay five thousand pounds in bail – an enormous sum for that time. Then, out of the frying pan and into the fire – Joseph Hall went to Norwich to take up his new bishopric. Norwich was loyal to Parliament and would raise troops for Cromwell in the soon-to-commence civil war. And Parliament had just voted to deprive Hall and his episcopal colleagues of their property and income, except for a shaky promise of annuities for their support.

Unsurprisingly, Bishop Hall was not allowed to remain unmolested in the Norwich cathedral. Parliamentary supporters came to seize his property, and to deface the “idolatrous” stained-glass windows and other papist-looking church fixings. Hall and his family were evicted from the episcopal residence, and ended up renting a house in nearby Heigham.

In Heaven Upon Earth, Hall had given this meditation to think on in times of prosperity: “what if poverty should rush upon me, as an armed man; spoiling me of all my little that I had, and send me to the fountain for my best cellar” – i. e., drink water from a fountain rather than getting a drink from his wine cellar – “to the ground, for my bed—for my bread, to another’s cupboard—for my clothes, to the broker’s shop, or my friend’s ward robe? How could I brook this want?” Hall didn’t have to sleep on the ground, but he had been obliged to rely on friends and supporters for his support as he once again took up his pen.

While Hall lived in retirement, the English Civil War raged and was followed by the kingless and bishop-less Commonwealth where “prelacy” (government of the church by bishops) was specifically denied the protection of religious freedom. Hall busied himself in writing religious works, of which he published several. In effect he was acting as a private person, though some dissidents from the new regime may have quietly recognized him as still the bishop of Norwich.

The dispossessed bishop made one final effort in healing the country’s religious divisions in a work entitled The Peacemaker. In this book, Hall distinguished between essential Christian doctrines and inessential doctrines about which quarrels were dangerous: “It is possible I may meet with some private opinion which I may strongly conceive more probable than the common, and perhaps I may think myself able to prove it so; shall I presently, out of an ostentation of my own parts (abilities), vent this to the world, and strain my wit to make it good by a peremptory defence, to the disturbance of the Church, and not rather smother it in my own bosom, as thinking the loss much easier of a conceit than of peace?” The government should not tolerate authors or preachers who disturb the religious peace – “how worthy are they to smart, that mar the harmony of our peace by the discordous jars of their new and paradoxal conceits!” Hall believed he had witnessed the link between verbal religious warfare and actual warfare, and he wanted to nip the evil in the bud.

Hall was eighty-two – quite an advanced age for that time – when he passed away in 1656. He had given Stoic advice for the alleviation of private and public disturbances of tranquility, and had met such disturbances in his own life.

Works Consulted

Geoffrey Aggeler, “‘Sparkes of Holy Things: Neostoicism and the English Protestant Conscience,” Renaissance and Reformation / Renaissance et Réforme New Series / Nouvelle Série, Vol. 14, No. 3 (Summer / été 1990), pp. 223-240.

Kenneth Fincham and Peter Lake, “Popularity, Prelacy and Puritanism in the 1630s: Joseph Hall Explains Himself,” The English Historical Review, Vol. 111, No. 443 (Sep., 1996), pp. 856-881.

Sarah Fraser, The Prince Who Would Be King: The Life and Death of Henry Stuart (London: William Collins, 2017).

Joseph Hall (R. Cattermole, ed.), Treatises, Devotional and Practical (London: John Hatchard and Son, 1834).

Joseph Hall and John Jones, Bishop Hall: His Life and Times (London: L. B. Seeley, 1826).

Frank Livingston Huntley, Bishop Joseph Hall 1574-1656: A Biographical and Critical Study (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1979).

Dan Steere, “‘For the Peace of Both, for the Humour of Neither’: Bishop Joseph Hall Defends the Via Media in an Age of Extremes, 1601-1656,” The Sixteenth Century Journal, Vol. 27, No. 3 (Autumn, 1996), pp. 749-765.

Max Longley is the author of Quaker Carpetbagger: J. Williams Thorne, Underground Railroad Host Turned North Carolina Politician (McFarland, forthcoming), For the Union and the Catholic Church: Four Converts in the Civil War (McFarland, 2015), and numerous articles in print and online.

[…] common characteristic of the Neo-Stoics I’ve profiled in pieces previously published (on Joseph Hall, Justus Lipsius, and George Mackenzie) is that they often seemed more interested in peacemaking […]