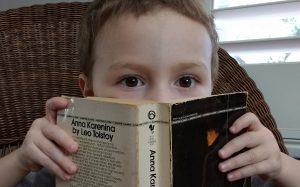

“All happy families are alike,” wrote Tolstoy in Anna Karenina, and “each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” When I first read this line as a teenager, I couldn’t understand what Tolstoy meant. How could there be many kinds of unhappiness, but only one kind of happiness? Don’t happy families have their own unique set of circumstances and characteristics, just like everyone else? In the novel he seemed to be saying that happiness is dull and uninteresting. It didn’t really make sense.

But as the years have rolled on, I’ve started to understand his point. Trying to create my own version of a happy family has made me think about what is absolutely required for harmonious relationships: respect, responsibility, commitment, compromise. Maybe this is what Tolstoy meant? Not that happy families actually do everything the same way, but that they have certain habits of mind that let them laugh, understand, and be comfortable with each other?

Stoicism throws a beautiful new light over the puzzle of family happiness. Of course there are secrets to a happy family–they are called the disciplines of desire, action, and assent. All the virtues that Stoicism develops in a person are also necessary for family harmony. And just as virtue can lead us to eudaimonia as individuals, a family might be called “a happy family” if its members have learned to be reflexively kind, wise, forgiving, and fair.

Granted, most happy families in the world don’t use Stoic terminology to describe their actions. They might not be able to clearly articulate how and why they get along so well, or they might use words from other cultural or religious traditions. But if you really examined their behavior, I’m guessing you would find these same virtues at the root of their contentment.

So how do we cultivate harmonious family relationships? This task is somewhat different from being a virtuous individual, because we clearly do not control our family members. We do not choose our relatives (except our spouses or partners), and most of what they do is outside of our control. Unlike personal virtue, family harmony is a preferred indifferent, albeit an important and highly preferred indifferent. So as we work toward family happiness, we have to remember that we can only do so much. Like the Stoic archer, we can aim for a happy family, but we cannot guarantee the outcome of our efforts.

What we can do is focus on our own contributions to family harmony. We can apply wisdom, fairness, generosity, and self-control to all our interactions with our loved ones. No matter what our family members do, or how they respond to our good intentions, we can still play our part well. Stoicism gives us all the mental tools we need to take a patient, rational, loving approach to our most important relationships.

With that in mind, here is a summary of (in my opinion) the most important Stoic advice on relationships. It revolves around three main points: amathia, emotional altruism, and your role in the family. If you genuinely put all these techniques into practice, you will be able to say that at least one member of your family (yourself) is truly happy with your efforts.

Amathia

Epictetus talks a lot about how no one tries to be wrong, but most people are simply ignorant of the right way to be happy. Everyone acts in the way that seems best to her or him. The problem is, most people think that their happiness lies in serving their own narrow self-interest. They might believe they are accomplishing their own best interest by pursuing external goods or shoring up their own egos. They don’t understand that true happiness only results from treating other people with fairness and kindness.

As Massimo Pigliucci points out in How to Be a Stoic, there is even a label for this type of un-wisdom: amathia. He defines it as “the opposite of wisdom, a kind of dis-knowledge of how to deal with other human beings” (p. 116). And we don’t need to limit this word just to people committing horrible crimes (Medea killing her children, for example). It also explains the petty cruelties that people inflict on each other in everyday relationships. Fighting, resentment, defending your own turf, intentionally misunderstanding, trying to control other people, choosing to take unnecessary offense. Even people who love each other often display this dis-knowledge of how to get along. It is all too human. In fact, this way of relating to others makes sense if you hold the mistaken belief that happiness lies in defending your own ego.

Because such people are incapacitated by their blindness, says Epictetus, we should pity them rather than resent or despise them. Especially when it comes to our most important relationships in life, we should try to understand rather than accuse. Which leads to the second important reminder…

Emotional Altruism

In his discussion on friendship, Epictetus tells us that a Stoic “will be tolerant, gentle, forbearing, and kind with regard to one who is unlike him, as likewise to one who is ignorant and falls into error on the matters of the highest importance” (2.22, 36). In discussing our relationships with others, he reminds us again that we shouldn’t be harsh with anyone, because people err against their will.

Marcus Aurelius, who also knew a thing or two about putting up with unpleasant people, goes further and says that we should treat others with genuine goodness, “with affection, and a heart free from bitterness.” (11. 18, 18). This is very, very hard to do. But if you truly internalize the Stoic position on virtue, then it becomes easier to stop defending your own position in an argument and start supporting your family member.

We should also remember that backing down from an unnecessary argument, or showing benevolence in other ways, does not make us weak or wrong. It seems to me that some people mistakenly believe that emotional generosity is equivalent to weakness or vulnerability. In fact, the opposite is true: “It is not anger that is manly, but gentleness and delicacy. It is because they are more human that they are more manly; they possess more strength, more nerve, and more virility” (Meditation 11. 18, 21). Strength (which obviously applies equally to women and men, despite Marcus’ identification with manliness) lies in wisdom and justice, while weakness lies in pettiness and selfishness.

Remember Your Role

We no longer live in the patriarchal society of ancient Rome (thank goodness!), so some Stoic advice on social roles does not apply to 21st century relationships. But some of it does. The underlying message is as relevant as ever: your mother or sister may mistreat you, but you should still remain a good brother or son to them. Other people, even your closest family members, cannot truly injure you. Your brother could steal your inheritance or your father could forbid you from studying philosophy, but you must still behave appropriately toward them. It is better to be the person wronged than the one who is wronging others.

Of course, things can get complicated if you’re not sure exactly what your role is. Many of us live in societies that have upended traditional social roles, which is mostly a very good thing. However, it can be a bit confusing to figure out how much deference you owe to your parents, or exactly what to expect from your own kids. So if you are a Stoic living in a non-traditional society, you’ll have to think carefully about your role in the family.

We should always approach our relationships with good-heartedness. But the way we apply our understanding will be different depending on the specific relationship in question. So let’s take a look at some of our primary family relationships and think about what a Stoic approach might be. Obviously, these are just some general observations, which might not apply to every family and every situation. (Contra Tolstoy, every family is different, even happy ones!)

The lens I’d like to use for this examination is one of Marcus’ maxims: “People were made for one another. So either instruct them or put up with them” (8.59). If you are fortunate enough to know the source of eudaimonia–virtue–then you can try to teach others. Or you can use your wisdom to accept them the way they are. But when do you try to teach, and when do you just accept?

The answer depends on many factors, from your position within the family to individual personalities and situations. But I would like to suggest that we can have a default answer to this question, which should guide our behavior most of the time. Here are some suggestions for how you might consider approaching three important family relationships.

Your parents (and other elders): Put up with them. Has anyone ever been allowed to instruct their parents in life? These days, we are no longer expected to “obey” our parents (at least, not after we move out of their house!). But even if our relationships today are more casual, we should still respect our parents’ position, and the love and care they have given us over time. Do you have to do what they ask all the time? Of course not. But when you disagree, disagree with respect.

Musonius Rufus gives excellent advice on this topic. In his lecture on whether parents must be obeyed in all things, he says that the dutiful son “obeys his parents when he willingly follows the good advice they give; and when they don’t give good advice, I say that he is nevertheless obeying his parents when he does what he should” (Lecture 16). His rationale is that all parents want what is best for their children, even if perhaps they do not actually know what is best. “Consequently, anyone who does what is appropriate and beneficial is doing what his parents want.” Continuing with this reasoning, Musonius says it’s fine to refuse to do something inappropriate that your parents ask you to do (or to do something appropriate that they forbid you from doing), because you are doing it out of goodness.

But like all forms of virtue, it’s about your motivation. You should make sure that you are acting virtuously, not out of selfishness or a desire to prove a point. And for all the unimportant things, try to put up with your parents’ quirks and flaws. (Remember amathia and emotional altruism.) Don’t you think you owe them that much?

Your significant other (and siblings): Instruct them and put up with them. Your life partner is your peer, so you are in a position to influence her or him for the better. If you show emotional generosity, your partner is much more likely to do the same. (If your partner is violent, abusive, or otherwise unethical, then of course you should take more extreme action.) But for all those run-of-the-mill strains on your relationship, it’s very helpful to take Marcus’ advice to heart. “If he is wrong, instruct him to that effect with benevolence, and show him what he has overlooked. If you do not succeed, then be mad at yourself [for not being persuasive enough]; or rather not even at yourself” (10.4).

In other words, try to bring your partner around to your way of seeing by explaining, persuading, and truly living out your beliefs. If that doesn’t work, don’t get angry. It’s not his fault that he hasn’t yet learned the right way to be happy. Stay patient and hold up your side of the relationship by being the best partner you can be. Remember that everything outside of virtue is indifferent. Those little things your partner does that drive you crazy are probably within the realm of indifferents.

However, do not use Stoicism as an excuse to stay in a toxic relationship. Remember that virtue requires courage, so if you need to end it, then be courageous about it. You can exit virtuously. You can practice wisdom and courage in any situation.

Your children: Instruct them. This one seems obvious. You have more influence over your kids than over anyone else in the world. What is less obvious is how to balance instruction with acceptance. Since you do not actually control your child, you can only do so much to mold her behavior. After you’ve done what you can, you still have to accept her imperfections. (And hope that, when she grows up, she accepts yours!)

Remember, the suggestions here are just basic guidelines and may not fit every family or situation. You have to use your wisdom to apply Stoic advice in real life. Just because your default mode of dealing with your parents is to put up with them, that doesn’t mean it will always be appropriate to accept what they do. There may be times when it’s better to try to instruct them. But if you decide to instruct them, you’d better have a very good reason.

With all that in mind, maybe we can revise Tolstoy’s quote to fit a Stoic perspective on relationships: All happy family members know how to relate wisely to each other, but each happy family can still be happy in its own way. This version might be much less poetic than Tolstoy’s, but I think it’s a good characterization of what to aim for in our own families. So as you sit down with your loved ones over the holidays–or any other time of year-remember that we were made for one another. We owe it to our families to at least aim for happiness.

Brittany Polat practices Stoicism daily with her three young children and describes her experiences at apparentstoic.com. Her book on Stoic parenting, Tranquility Parenting: Timeless Truths for Becoming a Calm, Happy, and Engaged Parent, is scheduled to appear in 2018.

Discover more from Modern Stoicism

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thank you for this. I have a difficult meeting coming up with a friend where I’ve upset her by challenging something she said. I want to be kind without caving to the pressure of “You can’t disagree with me or I’ll get upset and it’ll be your fault.” I’ve made a note to myself to come and reread this before we meet, because there’s a lot here I want to keep in mind.

Stoicism: always easy to say, always very hard to do! All I need to be is respectful, responsible, committed, willing to compromise, kind, wise, forgiving, fair, generous, patient, rational, loving, forbearing, not bitter and self-controlled in all my interactions with my loved ones!

Well-said, Ms. Polat. As a psychiatrist, I would probably be able to drop my family therapy hours, if every family imbibed the Stoic wisdom you describe!

Best regards,

Ron Pies

Ronald. W. Pies MD

Professor of Psychiatry

Very well written at a reasonably understandable level.l. Thanks. Too bad we are not exposed to the way of described living at an early age so we may hone our living skills. Happy day and Peace profound.

Loved this article – thanks Brittany.

Truly enjoyed your spin on family matters done the Stoic way. What of adult children. I know i can apply much of what you said but wonder if you have some additional insights?

Hi Story Explorer,

The ancient Stoics didn’t provide much advice in this area, but I think the dichotomy of control is very helpful in dealing with all children, from toddler to adult. Parents can’t control what their kids do. But what parents can do is influence their kids. My opinion is that with adult children, your primary influence is probably in being an excellent role model. Even if they don’t admit it, grown children often look to their parents as a reference for their own actions. If you continue living wisely and justly yourself, your children will be much more likely to do the same. After that, I think you can apply some of the ancient psychological insights to persuading your kids to act in a certain way. For example, we see Seneca (in On Anger) reminding himself, “In that discussion you spoke too aggressively: do not, after this, clash with people of no experience,” or “You were more outspoken in criticizing that man than you should have been, and so you offended, rather than improved him.”

Perhaps other Stoics have additional advice? Good luck!

[…] Happy Families: A Stoic Guide to Family Relationships by Brittany Polat […]