Falling into Stoicism

by Mark Leggett

“Do not dread death or pain- but rather dread the fear of death or pain”- Epictetus

Last year I read my first book on stoicism. One aspect that appealed to me was that those principles written about over 2000 years ago are still relevant today and can be experienced by normal people in their daily lives. In this article would like to relate an incident that occurred to me 16 years ago after which I ‘discovered’ some of the truths written about by the Stoics.

I had walked and run in the hills all my adult life but in 1998 was new to winter mountaineering. I had decided to climb Ben Macdui, Britain’s second highest mountain in February. In contrast to Ben Nevis (Britain’s highest mountain) which is only a mile or so from the town of Fort William, Ben Macdui stands in the centre of a vast wilderness known as the Cairngorm Mountains. I started my hike from the car park at Linn of Dee near Braemar one Saturday afternoon and camped overnight at Derry Lodge- a disused hunting lodge set in a small pinewood. I was disappointed to find it was raining at this low level.

The next morning I rose and packed away my soggy tent and made my way through the trees and then through the open moor of Glen Derry, soon I was above the snow line. Turning left I climbed to the Hutchison Memorial Hut. The small bothy (editor’s note: a ‘bothy’ is a small shelter) was occupied and filled by a German tourist who had loads of kit spread over every surface; snow shoes, crampons, ice axe, walking poles, tent, sleeping bag, stove- he had everything. I chatted for a few minutes then carried on climbing up to towards Loch Etchachan. The significance of this was that the German might have been the last person to see me alive.

The weather got steadily worse as I climbed; thick snow underfoot and high winds. It was bitterly cold. Loch Etchachan was frozen over and covered with snow.

After many years hiking in hills I knew I was not a natural navigator but I could use a map and compass. I followed the frozen stream bed that fed into Loch Etchachan until it petered out then continued on a compass bearing for the summit.

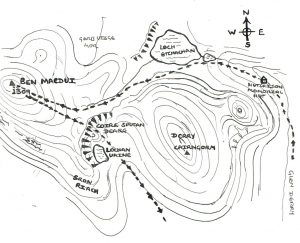

‘A map of the area in which Mark escaped death, and the route he took.

As I climbed the mountain the wind whipped the snow up into a fog until I was in a complete white out. A white out is similar to total darkness (an uncommon experience in our modern world where there is almost always some ambient light) only in a white out everything is white rather than black. The sky is white, the ground (covered in snow) is white and everything in between is white. Wherever you look its white – no horizon, no features, just white. Without any contrast or graduation in tone for the brain to use to detect distance or form one is effectively blind.

I religiously kept to my compass bearing and trudged blindly upwards. It took a while in the wind and snow carrying a heavy pack but eventually I was pleased to encounter the remains of a building – four low walls of dry stone half buried in the snow- that I remembered from previous ascents during the summer. I knew that this ruin was only a few hundred yards from the summit.

The summit was a wild inhospitable place. The trig point was completely encrusted in horizontal windblown icicles. It was extremely cold and blowing a gale. I didn’t stay long; no leisurely munching of sandwiches and admiring the view on this day!

I turned round and started my descent. All I had to do was reverse my compass bearing until I found the top of the frozen stream, follow that down to the frozen loch and then I would be safe. Buoyed up by my successful navigation on the way up, and having timed my ascent so I knew approximately how long it would take to get back to the stream, I was confident I would be ok.

However it all hinged on finding the top of the frozen stream which started as a mere depression in the snow. I had not considered how difficult (i.e. impossible) it would be to find this in white out conditions. If you look at a map of the area you will see that a change of direction is required at the stream because if one continues in a straight line there are some precipitous cliffs ahead. I descended until I was close to the point where I would have to turn, but became confused because I seemed to be climbing a mild incline. I say seemed to because in the white out conditions it was impossible to be sure, my legs were telling me from the increased effort that I might be climbing but apart from the compass in my hand I could see nothing.

Then I fell forward into the whiteness.

At first I thought that I might have tripped on a buried rock, or perhaps there was a small hole or dip in the snow, but when I carried on falling I knew what I had done. I had walked off the edge of the cliffs of Coire Sputan Dearg.

People asked me afterwards if I had fallen through a cornice of overhanging snow. Well I didn’t, I simply walked off a cliff because I couldn’t see the edge. I only fell for a second or two before slamming into the steep cliff side, bouncing, falling and bouncing again. I had seen these cliffs in the summer, I knew their height and steepness, I knew I was dead. This sounds dramatic, and obviously I didn’t die or I couldn’t be writing this, but at the time there was absolutely no doubt in my mind that I was about to die. It was NOT like being in front of a firing squad as the soldiers load there weapons ,hoping for a last minute reprieve, it was like being in front of a firing squad and hearing the command FIRE !, done deal ,no way out, end of story.

“Cease to hope…..and you will cease to fear. Widely different (as fear and hope are) the two of them march in unison like a prisoner and the escort he is handcuffed to. “ Seneca

I am not a brave person, and several times in my life I have got myself into scrapes in the hills and scared myself witless. I don’t like taking risks and would even describe myself as a timid person. Rock climbing for example is not my thing; it is far too dangerous and scary. However on this occasion I felt no fear. I was looking death in the face and my only emotion was regret that it was all about to end. I believe that if I had fallen but ended up clinging to a cliff edge by my fingertips, with the possibility of survival or death, I would have been terrified. But because I thought death was inevitable I was not afraid.

“It’s not what happens to you but how you react that matters” Epictetus

I bounced and somersaulted through the air several more times before finding myself spread-eagled on a steep snow slope. By amazing good fortune I had fallen in the one area where the cliffs are less steep. When I realised I was alive I felt tremendous relief and elation , my back was hurting, my face was damaged and I was alone half way down a cliff in the Cairngorms miles away from anywhere, but I was alive. I could feel liquid running down my face. It was clear rather than bloody and I soon found I had no vision in my right eye, maybe the eyeball had burst? No matter -I was alive ! Hours later I found out that my eye was ok but the right side of my face had swollen up clamping my eyelids shut so I could see nothing out of that eye.

I don’t know how far I fell or how close to death I actually was. I know people have died falling from smaller cliffs and others have survived far greater drops. For me the two relevant factors were the absolute certainty that I was about to die followed very quickly by the miracle of my survival.

I tried to climb back up the cliff, but soon gave up as it was too steep and I had lost my ice axe in the fall. So I descended down to the valley – not easy on the steep terrain and icy snow with no axe and only one good eye. Lower down I floundered my way through deep snow to Glen Luibeg. Soon it got dark and it took a long while but eventually I reached my car at Linn of Dee and drove back to Braemar. There after scaring the people in the village shop with my swollen and bruised face I wound up in the police station where the village Bobby, who was also in the mountain rescue team, gave me a coffee and got the local G.P to examine me. The doctor managed to prise my eyelids apart and it was then that I found that my right eye was intact. He suggested that I spent the night in Braemar and that he had another look at me in the morning.

When going to the hills alone I always leave details of my intended route with a friend or my parents and phone them when I am back in civilization. So I went to the telephone box and called my friend and told her that I had had a fall but that I was alright. I found a ridiculously cheap room in the local hotel and got some food. The room had a television which at that time I didn’t have at home , so it was a great treat to watch TV , I also had a bottle of whisky ( not ideal given the danger of concussion- but I was celebrating my survival ) so all in all it was a very pleasant evening.

When I got home the next day my friend told me what a terrible evening she had had, I was perplexed and asked her to explain. She told me that she had been very worried and upset after hearing about my fall and it had ruined an evening she had planned with friends. In contrast, I -the supposed traumatised victim- had a great time !

“If you are distressed by anything external the pain is not due to the thing itself but to your estimate of it; and this you have the power to revoke at any moment”. Marcus Aurelius

My face healed quite quickly although my right eyelid still droops when I’m tired, my back took months to come right, but apart from that I survived the incident unscathed. Overall it was a positive experience; I discovered that death is not necessarily a terrifying event but that it is the fear of death that is terrifying. By luck, on this occasion my opinion of the events was coloured by the seeming inevitability of my death and then my lucky survival. I learnt that day that it is not external events that cause mental anguish but one’s attitude to those events- and that is something that is in one’s own control. If I had been badly injured or permanently disabled by my fall I admit I might have been left with a different outlook but I think I would still have felt that overwhelming sense of joy when I discovered that I was not dead. It could so easily have been different.

Had I experienced fear or anguish I might have consequently had nightmares about falling and suffered post-traumatic stress. I might have never returned to the hills again. None of these occurred.

“It is not death that a man should fear. But he should fear never beginning to live.”

Instead that trip was the start of a love affair with the Cairngorms. Since then I have spent many carefree days wandering the tops in summer and winter. I learnt to navigate with more precision even in a white out (by counting steps to estimate distance). Some of the happiest times of my life have been on Ben Macdui and the surrounding peaks .I met my wife in the hills and a shared love of mountains help cement our relationship.

Of course I have a healthy respect for the dangers of hillwalking and running especially in the winter, and I definitely do not think that I’m invincible. In fact I do often contemplate death when in the hills especially after seeing a friend collapse and die on a mountain despite the desperate attempts of myself and others to revive him .I try to remember day to day how fortunate I am to have survived my fall and that all my life since then has been a bonus. I hope that when I do eventually meet my death I will be able to leave this world without fear or regret and without leaving behind too much hurt and pain. On that day on Ben Macdui I was doubly lucky , not only did I survive but I learnt a valuable Stoic principle. This was not through prior knowledge of the philosophy or through personal wisdom but sheer serendipity.

“When you arise in the morning, think of what a privilege it is to be alive, to think, to enjoy, to love.” Marcus Aurelius

Mark Leggett is a veterinary surgeon living on the west coast of Scotland. His passions are ultrarunning, mountains, and watercolour painting. He writes a blog. Mark did the artwork in this piece himself.

Discover more from Modern Stoicism

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Interesting article to which I can relate as my wife and I had a life threatening experience six years ago while boating and being “shipwrecked” on an isolated shore. We were eventually hauled to safety, from the foot of the cliffs, by helicopter. The stoic quotes in the article are well chosen and I can say that based on my experience.

I wish the article had paragraphs as the continuing block of solid print made reading and benefitting from it difficult.

My original article had lots of paragraph breaks – they must have got lost in the editing.

This is the second recent piece to appear on this blog with no paragraph breaks, which really diminishes the reading experience. It’s a disservice to the writers, especially those who contribute pieces gratis, to have their careful work presented this way.

You are right, Mark. This was an oversight, and will not happen again. Patrick Ussher (Blog Editor)

That was a lovely article, Mark. Weaving your experience in with the quotes made helpful and thoughtful reading.

I recall, many years ago, a chaplain at a hospice said that in his experience, people facing death were not so concerned at dying, as wanting to be reassured that their life had not been wasted. The emphasis in stoic thought of living life to the good, and to the full (rather than fearing death) is a good message to todays society. Truly stoic living should never result in a wasted life.

Mark: Thanks for the comment. I liked the article and found it helpful despite the lack of paras the absence of which, I guess, would be more of an irritant to you as the author than to your readers.

I enjoyed the article, too.

The paragraphing problem (and it is a deterrent for readers as well as an irritant for authors) is easily fixed, and needs to be. The webmaster/publisher simply needs to insert the proper paragraph tags and update the post; there’s nothing to it. Of course, all that should have been double-checked before the post was initially published. I was assuming the site owners would be following the comments here and quickly make the fix. Maybe they’re out for the weekend.

Mark L, if I were you I would email your contact at the blog and ask them to clean this up. Writing is a challenging enough enterprise without these kinds of disappointments.

Thank you for such an enjoyable account of your experience. The tension rose as I read, and the lack of paragraph breaks actually made it more dramatic to the point where I was gobbling up the words in anticipation of the conclusion! I am glad your devotion to the mountains remained intact. I shall be hill walking with my family in your beautiful country in August. We are in love with the mountains of County Kerry, Ireland in our homeland and can highly recommend them.

My sincere apologies to Mark for the errors in formatting. These have been corrected now. Patrick Ussher (Blog Editor)

Thank you for the changes, and thank you everyone for your kind comments.

Thank you for sharing your experience. It’s another reminder of how quickly we can be reminded that, no matter how well things may appear to be going or familiar the territory, we are all living on the “razor’s edge,” so to speak.

Saw the film Everest last week so your blog really resonated with me. I am struggling mentally at the moment so your words were very helpful and I will try to follow the advice. Thank you.