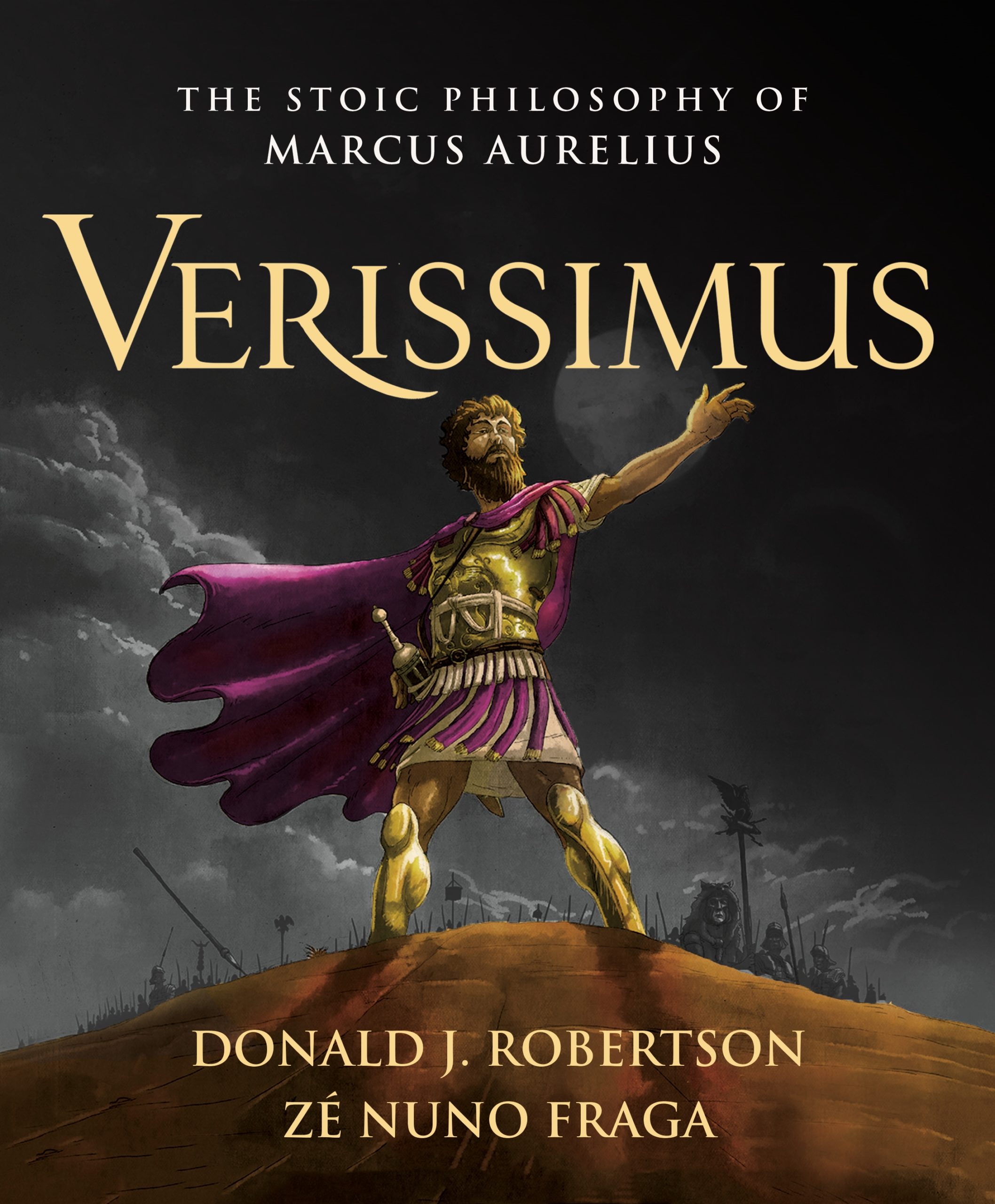

We editors of Stoicism Today – Harald Kavli and Greg Sadler – had the chance to send a set of interview questions to Donald Robertson about his new graphic novel, Verissimus (with artwork by Zé Nuno Fraga). He has very graciously provided a set of really substantive answers, which we hope you readers will find interesting and thought-provoking.

Stoicism Today: This might be a question that many have in their mind: Why a graphic novel specifically? What did you imagine or discover that format would provide that others wouldn’t?

Stoicism Today: This might be a question that many have in their mind: Why a graphic novel specifically? What did you imagine or discover that format would provide that others wouldn’t?

Donald Robertson: They say a picture is worth a thousand words. For many years, I worked as a trainer, teaching psychotherapists and counsellors, often discussing controversial ideas, over and over again. I found that people who are unconvinced by evidence and logical arguments often need examples, analogies, or vivid anecdotes. There are a handful of stubborn misconceptions about Stoicism, which are best dealt with in this way. For instance, the misconception that Stoics are cold and unemotional or that Stoic acceptance makes them passive in the face of injustice. Neither of these is true. It can be laborious trying to refute them, though, by arguing about the intricate Stoic philosophical system or the surviving textual evidence. It’s much easier to point to an example of a famous real-life Stoic whose life obviously disproves both misconceptions.

To put it another way, showing people, in a comic or movie, what Marcus Aurelius was like, allows us to give Stoicism a more human face. It encourages people to interpret the philosophy in a more realistic way by having them visualise what it might be like trying to follow Stoicism while surrounded by complex friends and enemies, in the midst of very challenging situations. As we worked on the graphic novel, I gradually realised that it allowed us to make more use of constructive ambiguity than a regular prose book might. We can even learn, for instance, from bad ideas or unconvincing arguments, if we view them from the right perspective. I think the visual format helps us to do that by placing certain words in the mouths of individuals whose judgement is not completely reliable, dealing with situations whose meaning remains opaque.

Stoicism Today: What was it like for you working with an illustrator like Zé Nuno Fraga? How did the process of collaboration work?

Donald Robertson: I’ve never met Zé in person – partly due to the pandemic. He lives in Portugal and, while working on Verissimus, I was mostly travelling between Canada and Greece. We communicated regularly online. Zé did concept art, I wrote a detailed script, he drew thumbnails, then pencil sketches, then inked and coloured pages. I gave feedback and suggested changes at each stage of the process, page by page, panel by panel. We worked with a freelance comic book editor, Kasey Pierce, now my wife. We also had a small team of advisors who helped us research the historical accuracy of military equipment, furniture, buildings, conversational language, etc. We also had support from a focus group of readers and, of course, our editor, Tim Bartlett, and the rest of the team and St Martin’s Press. Kasey likes to say it takes a village of people to make a comic or graphic novel – compared to writing a prose book, it’s often more of a collective effort. It’s usually assumed that writing a book will take roughly a year. I didn’t realize until we started but a graphic novel on this scale takes much longer. In our case, even working very systematically, to a tight schedule, it took more like 2-3 years to complete Verissimus. (The illustrator for Logicomix, the bestselling graphic novel about the history of modern philosophical logic told me it took them about seven years to finish!) The pandemic made some things difficult, especially travel, but luckily I’d already visited Carnuntum in Austria, where Marcus wrote part of the Meditations. While there I was able to shoot video, take photos, and interview staff at the museums, as part of my research, and that came in very useful during my work with the illustrator.

Stoicism Today: Besides telling a great story and teaching readers about Stoic philosophy along the way, what else did you hope or aim to accomplish in this graphic novel?

Donald Robertson: We wanted to make sure that if someone did really enjoy the book, even if they knew nothing about Stoicism, there might be at least one or two practical ideas they could take away and use in their own life. So that’s another reason we chose to focus on a specific emotion, and picked anger. We added a “cheat sheet” at the back to remind people of the ten different strategies Marcus used to cope with anger. And we also concocted a way of using a dream sequence in the story to further highlight those anger-management strategies. We wanted to make sure people noticed them, and remembered them, as much as possible, so that at least some of the readers might perhaps experiment with them in their own lives.

Stoicism Today: What led you to choose Marcus Aurelius’s life, thought, and words to focus upon for this graphic novelization, rather than, say, Epictetus or Seneca?

Donald Robertson: There are a few people out there who assume we know nothing about the life of Marcus Aurelius. Actually, we probably know more about him than we do about almost any other ancient philosopher, certainly more than we know about any other Stoic. His life was also very dramatic because he was such a powerful figure, surrounded by remarkable people, and he lived through such historic events: several great wars, and one of the worst plagues in European history. I wanted to write a graphic novel that really made full use of the visual medium so we chose Marcus because his story is obviously cinematic – actually we get an indication of that from the fact that Ridley Scott’s Gladiator tells the (mostly fictionalized) story of his death in its first act. The surviving Roman histories tell a complex story about Marcus that provides the raw materials for a sweeping historical epic.

We just don’t know as much about Zeno or Epictetus, unfortunately, and perhaps we could have told Seneca’s story but Seneca is, well, a much more compromised and problematic figure, I think, when you really try to visualize the story of his life. We have several very different sources of information on Marcus and that helps us to construct quite a complex and multifaceted story. Fortunately for us, the Roman historians were fascinated by several characters who play important roles in Marcus’ life, such as the Emperor Hadrian, Marcus’ adoptive grandfather; or Lucius Verus, his adoptive brother; Faustina, his wife; Commodus, his son, and so on. The colourful stories we have about these other people help us to recreate the “world” in which Marcus Aurelius actually lived.

Stoicism Today: Rusticus says to Marcus that “Philosophy is not just about books and lectures…” The Stoics were quite clear that philosophy is more about the way you live your life than about theorizing about the good life. But do you think that there is a healthy balance between a more practical and a theoretical approach to philosophy? Can we veer too much to the other side also?

Donald Robertson: In ancient Greek philosophy there was a contrast between two opposing views of what it meant to be a philosopher: Plato versus Diogenes the Cynic. Plato’s “Academic” school of philosophy emphasized scholarship, reading, debate, and quite abstract studies such as maths. Diogenes ridiculed the “Academic” lectures of Plato and his followers, and instead focused almost exclusively on developing self-discipline and strength of character. Zeno, the founder of Stoicism, began by training in Cynicism, but he then started attending lectures at Plato’s Academy, under his successors, and he also studied logic with the Megarian school and others.

I think that when he founded the Stoic school, Zeno must have said that too much “academic” philosophy can be a vice – it’s a type of folly to waste your life arguing over how many angels can dance on the head of a pin or, as Plato reputedly did, to try to verbally define a “human being” as a featherless biped. I think he also realized that ignorance of physics and logic is probably a hindrance. If nothing else, lacking a basic understanding of logic means lacking knowledge of the fallacies that Sophists may use to manipulate and deceive us. We need to defend ourselves, through education, against the persuasive power of rhetoric. We can imagine Zeno saying that study is only good insofar as it actually improves our character, and brings us closer to virtue and eudaimonia – whereas studying can be bad if it does the opposite.

I think we see that attitude in Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius, especially where Marcus – a massive nerd – talks about it being time to throw away his books, and so on. He clearly doesn’t mean that literally but, rather, he’s saying that he needs to exercise moderation by being more selective about what he chooses to read and study. His studies should not distract him from the goal of living in accord with virtue. He should stop arguing about what it means to be a good man, he says, and just be one. That’s a struggle for him, though, because he loves books.

Stoicism Today: I notice that you draw upon many passages from Marcus’ Meditations, some of which you place in the mouth of Marcus, but many more you have someone else saying to Marcus. It is a very interesting narrative approach, and it gives the sense that Marcus’ thoughts are not just his own, but draw heavily on wisdom derived from others. Was that a deliberate storytelling strategy on your part?

Donald Robertson: We inevitably talk about the Meditations as Marcus Aurelius’ thought, although, on reflection, we should be cautious in doing so. Often he’s known to be quoting or paraphrasing other authors, such as Epictetus, Heraclitus, and Euripides. But many more of the passages in the Meditations, I suspect, are unattributed quotes, or paraphrases, from other sources. Before writing the Meditations, Marcus had been studying Stoic philosophy, seemingly every day, for around four decades, under several of the leading Stoic teachers alive at the time. When we tell the story of Marcus’ life, in which we know these teachers feature very prominently, we have to visualize what they were doing – what did Marcus and Junius Rusticus, his main Stoic tutor, actually talk about?

Our best educated guess is that they talked about the books we know Marcus read and that they discussed some of the philosophical ideas that Marcus likes to write about, over and over again. So we showed Marcus talking to other characters about concepts found in the Meditations. I think it would be less interesting if the philosophy only came from Marcus, and harder to depict him undergoing change, being on a personal journey. I slowly realized that the graphic novel was allowing us to imagine Marcus in a way that felt more human, more realistic, and part of that was visualizing that he was not the only philosopher, and that the ideas he was writing were probably sometimes ones he’d heard from his friends – he may even, at times, be writing down ideas he found problematic or hard to digest, right?

Stoicism Today: In the novel, I got the impression that Marcus came up with the idea of writing a philosophical/therapeutic journal. Do we know if Marcus was inventing a new genre of literature, or was philosophical journals already an established genre when he wrote it? Also, do you think that Marcus had any intention of publishing the book?

Donald Robertson: I’m not sure if “journal” is the right word if that implies something that’s written each day, and involves reflecting primarily on recent events or personal experiences. It’s possible that’s what Marcus was doing but we can’t be certain. It could be that he wrote chunks of the Meditations whenever he had time or that his reflections were not directly based on the events of the preceding day. It’s similar to a journal perhaps, and could be one, but it might not be. I doubt this was a genre Marcus can be said to have invented – compiling notes, sayings, quotes, and reflections seems to have been a familiar form of writing. Epictetus tells his students, for instance, to write about Stoic teachings. We can actually see Marcus Cornelius Fronto, Marcus’ Latin rhetoric tutor, telling him in several letters to practice taking philosophical sayings and phrasing them in several different ways, until he finds the right words to articulate them clearly. So it’s very tempting to see the Meditations as Marcus still following Fronto’s advice, several decades after those letters were written.

I don’t think Marcus intended to publish the Meditations. We are told by the (not entirely reliable) author of the Historia Augusta that Marcus read some of his philosophical writings aloud at Rome before leaving for the Second Marcomannic War, but this sounds like it may refer to a different work titled “Precepts of Philosophy” or “Exhortations”. There are several reasons why most scholars doubt Marcus intended to publish the Meditations. I can’t cite the evidence in full here but I’ll state the concerns briefly. First, Marcus says (or implies) several things that would probably have been too controversial or offensive to publish, given his position in Roman society. Second, he says a few things that it seems only he would understand, such as fleeting references to the content of private letters or conversations. Third, the writing in some passages appears far more polished than in others, giving it the appearance of private or unedited notes rather than a work ready for publication. You could add that there’s a lot of repetition and that it lacks the sort of structure we might expect in a work intended to be published, such as a more consistent approach to grouping topics.

Stoicism Today: There are many antagonists in this story, but none of the rivals, opponents, or enemies of Marcus seem to be villains in a classic sense. Is that reflective of Marcus’ own views on matters?

Donald Robertson: Yes, indeed. I’ve always thought “pure evil” was a ridiculous motive for a character! It’s very childish, in a sense, to tell a story in this way, with classic good guys versus bad guys – although we all enjoy stories like Harry Potter which largely operate on this level. Marcus, though, was a magistrate. In addition to studying philosophy he also immersed himself in the study of jurisprudence, the study of law. He presided over many legal hearings, even as emperor. He also held countless meetings with the chieftains and envoys of enemy tribes, exercising his talent for diplomatic negotiations.

I think Marcus understood human character better than most people today can even imagine. He did not view the “barbarian” rulers with whom he was at war as the bad guys. Neither did he view the Roman statesmen who led the civil war against him as bad guys, even though they most likely would have threatened to kill him and his family. Marcus talks throughout the Meditations about our duty to view others as our kin, our brothers and sisters, and to avoid hatred or anger toward them. He virtually only mentions Roman citizens once or twice, though. He’s usually talking very generally, about all human beings, even the Parthians and Germanic and Sarmatian tribesmen. They are also his brothers and sisters, in the cosmopolitan sense – they’re all fellow citizens of the same universe. In fact, he specifically says he’s not talking about bonds of “seed” (family bonds) or bonds of “blood” (racial bonds) but rather bonds of human nature (Med. 2.1).

Marcus knew that people are complex and he reminds himself in the Meditations that one way of correcting his anger is to tell himself that judgments about other people’s intentions can rarely be made with certainty and that their actions are often due to underlying motives that remain hidden from us. No man does evil knowingly, he says, citing Socrates. The “bad guys” believe that, in some sense, what they are doing is justified – they think Marcus is the “bad guy” – but Marcus, to his credit, very much understood this.

Stoicism Today: In Marcus’ speech to his soldiers at the beginning of Cassius’ rebellion, Marcus says “Indeed, Cassius may already have changed his mind on hearing the news that I am alive, for surely he would only have had himself acclaimed emperor presuming I was dead, after my recent illness.” Do you think that there is any chance that Marcus was right about that? That Cassius was perhaps a dutiful citizen who only let himself be proclaimed emperor in order to prevent Rome from descending into the chaos that would have ensued had Marcus died while Commodus was still too young to rule?

Donald Robertson: This speech, in Verissimus, is repeated almost verbatim from the account in Cassius Dio’s Historia Romana. Although some scholars have questioned its authenticity, I think it’s quite beautifully written and it would be surprising if Dio had completely fabricated something of this kind, given that many of his contemporaries would be familiar with Marcus’ public speeches about matters such as the civil war – it’s likely Marcus’ most important speeches were widely circulated and read long after his death. So my view is that even if Dio wrote this speech it must have sounded very plausible to his readers and close to things they already knew Marcus to have said.

I do think it’s a possibility that Avidius Cassius believed Marcus was on the verge of dying. In a situation like that, we can imagine Cassius being assured by his spies and informers that Marcus was dying. We can also imagine him concluding that he would have to act quickly and seize power before someone else did. Or maybe he saw it as an opportunity, whether or not Marcus survived, to portray him as too frail to continue ruling. Perhaps Cassius was deceived by others who wanted him to act for their own reasons, and may have exaggerated how ill Marcus was. I doubt we can say that Cassius was entirely a “dutiful citizen”, though, as he could probably have backed down when Marcus responded but he refused to do so. I also suspect that Cassius and others in his faction were the source of most of the gossip about Marcus and Commodus, especially the stories about Faustina’s infidelity, which seem obviously concocted to cast doubt in the legitimacy of Commodus, and thereby undermine his claim to the throne. If Cassius was spreading propaganda, he probably wasn’t acting in a completely innocent way.

Stoicism Today: In the graphic novel, when Marcus is mourning his son, we learn that one of Rome’s mythic kings, Numa, recommended that the Romans ought to mourn for 7 months after the death of a 7-year-old son. I was quite intrigued about the concept of mourning for a set time, and I was wondering how feasible something like that would be, at least on an emotional level. But then I thought about a technique in CBT where you are supposed to worry about your problems only at a specific time of the day, and there seems to be a similar idea. Granted, Numa could have had certain actions associated with mourning in mind, rather than the emotional aspect of morning. Still, do you think it could be advisable to try to deal with the loss of a loved one by setting aside a certain time interval for mourning?

Donald Robertson: Yes, that technique is called “worry postponement”. Worry is a pattern of thinking that typically accompanies anxiety, although this technique is also used to deal with other, similar types of thinking such as depressive rumination. If we focus on the example of depression, it becomes easier to see how it might help some people who are bereaved. I think it also helps to view this as an extension of normal emotional processing. By that I mean that people normally suspend prolonged thinking, when circumstances require them to do so. In order to get to sleep at night, for instance, you probably need to stop worrying and ruminating, and most people are actually quite capable of doing so. If you have to attend a job interview, likewise, you’re going to need to temporarily set aside worry and rumination. In fact, countless ordinary situations require our attention and it’s therefore perfectly natural to suspend worry and rumination so that we can deal with what’s going on for us in the real world. On the other hand, it’s unhealthy for us to keep doing this as a way of avoiding processing our upsetting feelings. There’s a healthy middle ground, in other words, that consists in spending some time thinking about the things that upset us, but not too much time, and being able to choose situations where it’s appropriate rather than allowing these thoughts to take over when we need to give our attention to other things. Pathological worriers, for instance, often lay awake at night and cannot easily get to sleep because they’re too busy thinking about stuff that makes them anxious. That’s not the norm, though – we’re usually able to let go of things when required to do so. Our natural ability to start and stop thinking allows us to gain cognitive distance, i.e., to view our thoughts and feelings in a slightly more self-aware and detached way, and that can help us process our emotions properly instead of being overwhelmed or controlled by them. I think the Stoics actually understood this as, for instance, Epictetus explicitly tells his students that when they feel themselves being overwhelmed by an unhealthy passion – such as worry, greed, or anger – they should let it go for a while and come back to think about it later when their feelings have calmed down.

Stoicism Today: This graphic novel portrays Marcus as struggling the most with his own anger. You could say that it is the most difficult long-term challenge he faces. It comes up at many points in the narrative. What led you to view Marcus in that way?

Donald Robertson: I think many people who study the Meditations closely come away with the feeling that Marcus is trying very hard to work on himself – he’s on an epic self-improvement quest. To understand that we have to understand the problems on which he was working. Marcus makes it very clear that he considers himself flawed – in fact the Stoics insist that nobody is perfect. Marcus expresses many criticisms of himself in the Meditations. He yearns to become better, more like Antoninus Pius, his adoptive father and predecessor as emperor. Sometimes he’s a bit vague about exactly where his own weakness lies but I believe there are enough clues to tell us that anger was one of the main issues he struggled with. He actually praises his grandfather’s “freedom from anger” in the very opening sentence of the Meditations. Anger turns out to be one of the main recurring themes throughout the Meditations, if you look closely he returns to strategies for coping with this emotion many times and at one point he actually lists ten different anger-management strategies (11.18).

There must be a reason he put so much effort into studying so many ways of coping with his own anger – the most obvious explanation is that he experienced an ongoing struggle with his own anger for many years. He confirms that he had anger problems early in the Meditations, when he says that he’s thankful he never lost his temper and did something he might have regretted, although he had the potential to do so (1.17). Marcus even hints at the reason for his anger elsewhere – he believes he’s surrounded by many people who do not share his values, i.e., there’s a clash between his morals and those of other powerful Romans. Of course, after he wrote the Meditations, this would be proven by the fact that one of his most senior generals, Avidius Cassius, supported by other powerful figures in the senate and military, conspired against Marcus, and instigated a civil war.

We also wanted to avoid the graphic novel being too much talk and not enough action. So we chose to focus on anger because, in a sense, it’s the most visual and dramatic of all emotions. Depicting anger is fun – it lends itself especially well to the medium of sequential art. Anger is more interpersonal than other emotions – we often get angry with other people and express our anger toward them, sometimes through violent facial expressions or even violent actions. That’s basically the stuff of which comic-books are made. I also believe that anger is the royal road to self-improvement, especially today. The Internet is awash with self-help advice, right? (A lot of it is actually garbage – psychologically very bad, counter-therapeutic advice.)

Despite the modern preoccupation with self-help, very few people do anything to address their anger. You may even have noticed that some self-help gurus are quite angry themselves and attract a following of angry young men, or women, who only seem to get angrier, ironically, the more “self-improvement’ advice they consume from these sources. And they just get angrier and angrier rather than less angry, although they’re supposed to be on a self-improvement trip – weird, huh? The Stoics realized that anger is the most dangerous emotion and it was their clinical priority to tackle it through their psychotherapy. (We even have an entire book on Stoic psychotherapy for anger that survives today, written by Seneca.)

Stoicism Today: Finally, in the afterword you write that this project has made you see Commodus in a different light. I was wondering if there are any other aspects of Marcus’ life that you have gotten a new perspective on while working on this project?

Donald Robertson: Yes. To cut a long story short, I believe that Marcus employed a method in writing the Meditations that led to the content becoming more abstract, in a sense, and detached from the specifics of his daily life. He followed Fronto’s advice to rephrase ideas repeatedly, trying to find the perfect words to express himself. That typically makes it easier for us to imagine how his reflections might apply to our own lives but it can also make it harder for us to imagine how these ideas were actually applied by Marcus in practice.

As Ze began trying to illustrate Marcus’ life, it became more and more obvious that he was surrounded by a bunch of very colourful, larger-than-life characters – the Emperor Hadrian, Lucius Verus, Faustina, Avidius Cassius, Commodus, and so on. They’re very dramatic people and, of course, Marcus’ life, outwardly, is defined by his interactions with them. That colour is the main thing that’s missing from the Meditations. We tend to imagine Marcus sitting by lamplight in his private chamber, patiently writing the Meditations in solitude. In reality, he also spent his days talking to, and trying to deal with, a whole cast of very dynamic personalities. Marcus’ life, to put it bluntly, was pretty crazy.

In a prose book we tend to fall into the trap of describing events more episodically. For instance, in one chapter we might talk about how around 166 AD the Antonine Plague began, then in the next chapter, we forget about that and start talking about the wars that followed. However, the plague continued, we think, until after Marcus’ death. Likewise, other events overlap more, and permeate different chapters in the story. It’s easier to imagine this when we look at events visually, in a movie, perhaps, or a graphic novel. So, if we’re lucky, we end up with a more complex, nuanced, rounded, and realistic impression of the subject’s life – and in this case, I hope that’s what we’ve given our readers with regard to the life of Marcus Aurelius. I think it also becomes more obvious, when we visualize Marcus’ story in this way, that he faced reminders of his own mortality much more often than most people would today. That’s one of the reasons why he is able to speak to us so profoundly about death.

Stoicism Today: Is there anything else that you wish you and Zé would have been able to put into the graphic novel that didn’t make it in? If so, what is it, and why would you like to have included it?

Donald Robertson: I originally included a scene about Justin Martyr and the alleged persecution of Christians during Marcus’ rule but there were reasons why that had to be dropped, unfortunately. I’d like to have had more long-shots of major battles but I now realize there are some technical challenges in doing that artistically (although we did get a lot of that sort of stuff in by using some tricks of the trade). Too much more of that would perhaps have caused pacing issues in relation to the other aspects of the story, though. There are a few other characters it might have been nice to include but I think then we’d have potentially complicated things for readers, and confused the story. So at times we did simplify a bit – we mainly focus on two of Marcus’ Stoic teachers, although he had others. There are complex questions about Christianity in the empire at this time and Marcus’ relationship with Hadrian and Commodus, which I’d liked to have explored but I don’t think this was the right medium. I’ve delved into those topics more in my prose biography for Yale.

Stoicism Today: I remember having conversations with you about two of your book projects – this one Verissimus, and your earlier book How To Think Like A Roman Emperor – as you were in early stages of thinking about them. You certainly have a drive to realize projects fully. So. . . is there any other new book project that you’re now talking about?

Donald Robertson: I just finished writing a prose biography of Marcus Aurelius for Yale University Press’ forthcoming Ancient Lives series, which should be due out next year, I think. So that’s three books about Marcus Aurelius in a row! To some extent that’s because it’s what the publishers were most interested in having me write. Although I really enjoyed spending so much time on Marcus, I’m also glad now to be working on a book about my other favourite philosopher: Socrates. I’ve got a hunch that might end up being two books about Socrates but it’s too early to say for sure… Maybe another graphic novel if Verissimus does okay!

Donald Robertson is a cognitive-behavioural psychotherapist, trainer, and author who specialises in the treatment of anxiety and the use of CBT and clinical hypnotherapy. He is the author of many articles on philosophy and psychotherapy in professional journals. Two of his more recent books include How to Think Like a Roman Emperor & Teach Yourself Stoicism and the art of Happiness (2013). Read more about Donald’s work on his blog, The Philosophy of CBT.

Discover more from Modern Stoicism

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.