Background: This is a revised version of my Stoicon speech in Athens, October 2019. For enjoyment purposes, imagine you’re sitting in a comfortable seat in the beautiful Cotsen Hall in Athens. You’re attending Stoicon and are excited for the first speaker, Jonas Salzgeber.

Introduction: Start with yourself

Just like my brother and me, many of you flew here in the last days. And what did they tell you on the plane? To put your oxygen mask on first, in case of emergency. Now, this is crucial advice not only on the plane, but for life in general. We’ll get to the reason why in a moment. But first, let’s go on a short flight together.

“Kh-kh, this is your captain speaking. Fasten your seatbelts and get ready for take-off.”

“So where are we flying,” you’re wondering?

We’re flying to the small and desert-like island of Gyaros. It’s only 96 kilometers away. That’s around half an hour plane ride with our small plane. We’re going there to meet one of the most important Stoic teachers from ancient Rome – Gaius Musonius Rufus. Now, Rufus wasn’t on this desert-like island for holiday purposes. He was the most prominent Stoic teacher and had respectable influence in Rome at the time. Too much influence actually for the tyrannical Emperor Nero, who exiled him to Gyaros in the year 65.

Now imagine this. Imagine you’re at your peak in Rome with a remarkable influence, life is pretty good, and you get kicked out, you’re exiled, you go from Rome at its peak to some desolate island in the middle of nowhere. How would you respond to that?

Well, if you’re a Stoic philosopher you’d respond with taking responsibility and looking after yourself properly. That’s what Rufus did. He took exile as an opportunity to practice courage, justice, and self-control. Exile doesn’t prevent anyone from practicing these virtues, he said.

Even if they take away everything you have, they can’t take the most important thing which is the ability to choose how you respond to the situation.

And nothing outside of you ever dictates your happiness. It doesn’t matter where they put you, you’re still responsible for your own happiness as well as unhappiness. So Musonius Rufus took responsibility for his life, even in exile. He looked after himself properly, even on this desolate Greek island. He didn’t choose to be there, but he chose to take responsibility and make the best given the circumstances.

Now that’s inspiring.

So, Rufus was first exiled in the year 65. This was actually a very challenging year for Stoic philosophers, because it was the same emperor Nero, who ordered Stoic philosopher Seneca to commit suicide, in that same year 65.

And it’s Seneca’s words that help me get back to our flight route. He said, “Our fellowship is very similar to an arch of stones, which would fall apart, if they did not reciprocally support each other.”

Let’s imagine an arch of stones. And all stones are supporting each other. Now, if I’m a stone in the middle of this arch and support one neighbor, and another, and maybe even another one further away, suddenly I’m the stone that breaks apart. And with me the whole arch. Because I’m not looking after myself properly.

If our fellowship is like an arch of stones, then each stone needs to start with itself. That’s its primary responsibility. Otherwise the arch will crumble. And by successfully looking after ourselves, we will support each other naturally.

Therefore, if we want to flourish collectively, as an arch, we need to start with ourselves and look after ourselves properly. We must take responsibility, like Rufus did in exile on Gyaros. So, let’s start with ourselves. In life, as on the plane, let’s put our oxygen masks on first.

Part 1: Basic Stoicism – We Are Response-Able

Now, with that arch of stones in mind, it’s such profound wisdom from the Stoics that brought us here together. That’s what we have in common, we’re interested in Stoic philosophy. So, in a way, and we might don’t want to call ourselves this way, we’re all philosophers. Which translates from the Greek into “lovers of wisdom.” We all want to attain the wisdom necessary to live properly, so that we can collectively flourish, right? And Stoic philosophy can actually help us do that. So let’s look at some basic Stoicism.

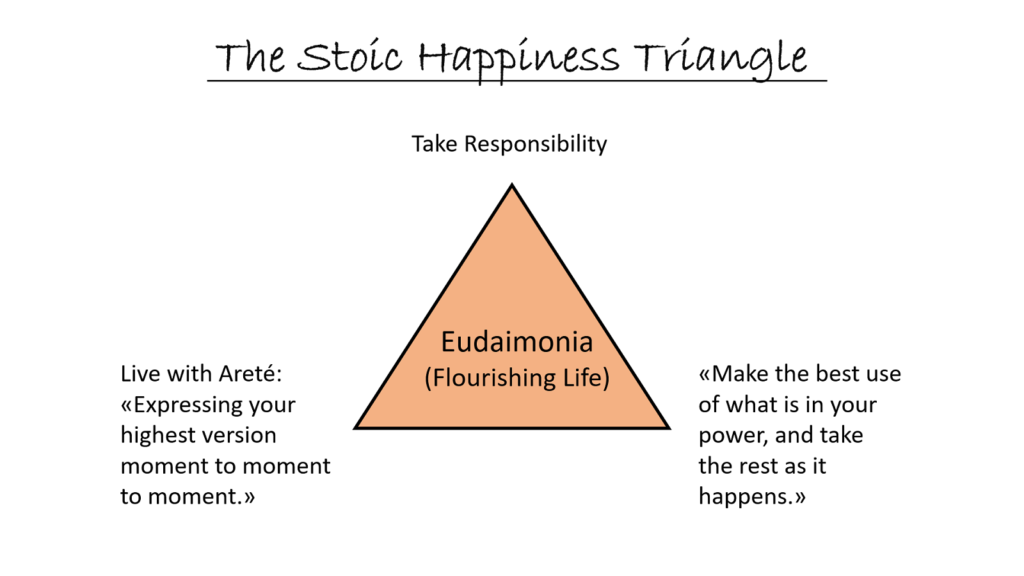

The Stoics had an overarching goal of life. It’s called Eudaimonia and comes from the Greek. Eu-daimon-ia – it means being on good terms (eu) with your inner daimon. The ancients believed that we have an inner daimon, a highest self, an inner spirit, or a divine spark within all of us. And if we’re on good terms with our highest self, that is, if we live out our very being, then we will flourish in life.

Eudaimonia often gets translated as happiness, but it’s more like flourishing or thriving in life. The Stoics’ goal of life was living out our inborn being, this highest self, or daimon. So, we’re here for the right reason: we want to learn how to flourish in life together.

The Stoics used another Greek word to show us the way to get there, to flourish in life. Areté is that word. Its most common translation is virtue, but at least for me, virtue is hard to grasp. And luckily, there is a profounder meaning to the word areté, which I learned from modern-day philosopher Brian Johnson. He says areté is “expressing the highest version of yourself moment to moment to moment.”

When undertaking an action, think about what your best self would act. That’s living with areté: expressing our best self… moment to moment to moment.

And the Stoics had a simple strategy to navigate through life and express that best self in every moment. That strategy is: “Make the best use of what is in your power, and take the rest as it happens.”

That’s the central teaching of Musonius Rufus’ most prominent student: Epictetus, who studied under Rufus and became a famous Stoic teacher himself. Like his teacher Rufus, Epictetus was exiled from Rome. So he moved to Nicopolis, which was a big city of the Roman Empire, it’s only around 400 km north-west from Athens, here in Greece. In Nicopolis, which by the way means “City of Victory” in Greek, he built his own school and taught Stoic philosophy to students who came all the way from Rome.

Now, if you look at the image of this blog post, you see The Stoic Happiness Triangle. We created this visualization of the Stoic core principles for my book, The Little Book of Stoicism. I mention it because this book is the only reason I’m standing here today. Donald Robertson somehow heard about the book and decided to invite me to Stoicon. Thank you.

Speaking of Donald Robertson… It was in his book Stoicism and the Art of Happiness where I learned about a beautiful metaphor the Stoics used to explain this second corner. The metaphor is from the founder of Stoic philosophy, Zeno, who taught here in Athens more than 2000 years ago. It goes like this: The wise man is like a dog leashed to a cart, running alongside and smoothly keeping pace with it, while a foolish man is like a dog that struggles against the leash but finds himself dragged alongside the cart anyway. Either we accept what happens, run alongside smoothly, and try to make the best with it, or, we complain about the situation, get miserable, and get dragged behind anyway because we cannot change it.

It’s wiser to accept your situation, and try to make the best with it. As in Epictetus’ central teaching: “Make the best use of what is in your power, and take the rest as it happens.” The Stoics said that it’s not what happens to you that matters, but what you do with it. How you respond. It doesn’t matter where that cart is going, what matters is how you respond to the situation.

That’s where the word responsibility comes from. It’s our ability to choose how we respond to what happens. Response-ability. And it makes the final corner of the Stoic Happiness Triangle. It doesn’t matter what happens to you, you are asked to respond properly. That’s life.

Viktor Frankl, the famous Nazi death camp survivor and founder of Logotherapy, said that’s where the meaning of life can be found.

Life ultimately means taking the responsibility to find the right answer to its problems and to fulfill the tasks which it constantly sets for each individual.

And these tasks are unique for each of us. He said that we are all questioned by life with the tasks it constantly sets for us, individually, and we can only respond by being response-able. And that’s classic Stoicism. They taught that happiness and unhappiness lie in how we respond to events. In what we do with the given circumstances.

We must realize that we are not victims to what happens to us, we are challenged. The Stoics didn’t behave like victims when they were exiled. They saw in it the very meaning, and an opportunity for growth, to practice their virtues. They took responsibility when they were exiled. They didn’t complain, but accepted their situation. They ran alongside smoothly and found opportunity in what might have looked like disaster to others.

And you see, such acceptance of the situation has absolutely nothing to do with resignation. It’s the opposite. It’s pure responsibility. Ok. I’m exiled, what now? What can I do with it? How do I respond? And look, we won’t get exiled to Gyaros or some other place. That’s not the kind of challenge we’re facing today. But what else is exile than a situation we don’t like, or that we didn’t choose? In a way, we’re exiled all the time. Many things happen to us that we don’t particularly like, sad things, and either we run along smoothly or we get dragged behind. Miserably.

So how do we respond to such challenging situations? Life is asking you, how do you respond? You can only respond by being responsible, by taking responsibility for yourself.

That’s ultimately what Stoicism is all about. And we don’t need to go over this triangle again, because it just screams out one message, which comes from Epictetus: “If you want anything good, get it from yourself.”

That is, take responsibility for your life. Remember the arch that crumbles when you fail to look after yourself properly. It’s not what happens to us that matters, but how we respond. That’s the key here. And we need to start with ourselves. That’s our primary response-ability.

Part 2: Take Stock and then Aim Up

So, our primary response-ability is to look after ourselves. So that we each stand strong and can flourish together, like an arch of stones. And the Stoics gave us countless strategies on how to do that. We’ll stick to the basics today. Because if we understand the basics properly, that’s enough. Epictetus said it simply: “First say to yourself what you would be; and then do what you have to do.”

The first part of this quote contains two points. Because before we can tell what we would be, we need to take stock. Where am I now? And only then can we say where we want to go. So, we’ll start here: Where am I now? Or who am I now, at this stage in my life?

To explain this simply, let’s look at a room. Okay, that’s my room. What can I see? I see a bed, not done. The blanket just lies in the middle of the bed. What else? I see a desk and a chair. The desk is full with stuff, letters and books, and clutter. The chair is full with clothes. And then the wardrobe. It doesn’t even close. It’s so stuffed with clothes and shoes.

So, that’s the first thing we do: We take stock. That’s my room right now. Or, that’s me right now. That’s what I spend my time with, and that’s how my relationships look like, or, that’s how a usual day in my life looks like.

Now, second step. Where do I want to go? Who would I like to be, and what would I like to do with my time? And if we look at the room, how would I like the room to look like?

Well, the bed looks nicer when done. And I want to work on the desk, so I need to clean it. Then I want to sit on the chair, so I have to put the clothes away. But the wardrobe is already full… So, let’s start with the wardrobe. It’s full with clothes I haven’t worn in years. What could I do? Clean it up, give some clothes to charity or to friends or throw them away.

The point is that we see where we want to go. With the room, it’s the same thing as with our life. It’s just an example. This isn’t about cleaning up your room, it’s about cleaning up your life. And taking responsibility for yourself. But the room might be the best place to start. Maybe the room is a good mirror of where you are in life. It might reflect well where we are.

So, I’m here now. Where do I want to go? I want to aim up, because I want it better, not worse. That’s why we aim up. That’s the first part of Epictetus’ quote: “First, say to yourself what you would be,” and only then can we do what we have to do.

What we do here, is basically revealing that we’re not where we’d like to be. It reveals inadequacy. That might hurt. But it’s necessary. Because we first need to acknowledge that we could be more. These are the first steps. I’m here now, I want to go there. So we need an aim. That’s why I say, aim up. We need an aim, something to shoot at. We cannot navigate through life without something to aim at. As Seneca said: “If a man knows not which port he sails, no wind is favorable.” We cannot navigate without something to aim at.

And with the room, that’s easy. But with ourselves, that’s much harder, because we are too close. So, what I find helpful, is to ask myself, what would you recommend your friend, or partner, or child, someone important to you. Someone you only wish the best, someone you wish to improve, and be their best.

So, I wouldn’t recommend my friends to watch Netflix every night. I wouldn’t recommend them to eat junk food. I would recommend to clean up their room, read a book or go to the gym instead of watching TV, and eat more vegetables, go to bed earlier, and get up at the same time every day, so they have a better rhythm. All those things.

And what we’d recommend to the people we love, we could also recommend to ourselves. Because what’s good for them might be good for us too.

That’s very simple. To see at least partly where we want to go.

But putting it into practice? That’s much harder. That’s the second part of the Epictetus quote. First say to yourself what you would be, we’ve done that, we have an aim, and then do what you have to do.

How can we do what we have to do? The Stoics say we need to regulate our impulses. So that we’re actually able to respond by choice, instead of reacting automatically. A reaction is reactive. It comes from the outside. Something outside happens, and we react. That’s impulsive, coming from the outside. Our response, however, is coming from us, from the inside. And we can choose it. We need to choose our response. That’s our most precious ability. Our response-ability. As Epictetus said,

Be not swept off your feet by the vividness of the impression, but say: ‘Wait for me little impression: allow me to see who you are, and what you are an impression of; allow me to put you to the test.’

“Wait for me little impression.” If we wait, we do not react. We pause. With awareness in the situation. And from there, we choose our best response. Or what we think is best. This requires awareness. Or mindfulness. Or attention as the Stoics called it. And how can we improve our mindfulness? Meditation is a good start. And personal reflection.

Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations are nothing else than personal reflection. A journal to himself. What did he do well? Where could he improve? Who does he want to be in this world? That is Stoicism. To look at yourself, to take responsibility for your life, to look after yourself so you can be your best version, moment to moment to moment. We need to reflect. And catch ourselves where we went wrong, so we can correct it. And aim up.

We can start small. Ask your emotional brain, what are you willing to do? I know you don’t feel like doing this, but hey, we want to move forward. We’re aiming up. So, what are you willing to do? Ask yourself, what could I do, that I actually would do? And then do it. Start small. Start with the wardrobe. Or start with the t-shirts. Whatever you can bring yourself to do. What could I do, that I would do? And then do it.

And of course it’s hard, we’re aiming up. Going up is hard by definition. If you want to climb a mountain, you don’t think this will be easy. It’s not. You expect it to be hard. You will struggle, and sweat, and fall. That’s part of the climb. And yet you continue. It’s the only way, to go up.

So… First say to yourself what you would be, then do what you have to do. I’m here now, I want to go there, so I have to do this to get there. And this last part is really hard. And it’s supposed to be hard. That’s what we’ll look at right now.

Part 3: Challenges Are Necessary for Growth

What would have become of Hercules, do you think, if there had been no lion, hydra, stag or boar – and no savage criminals to rid the world of? What would he have done in the absence of such challenges?

That’s what Epictetus asked his students, probably when they were complaining about their hard lives.

“Obviously, he would have just rolled over in bed and gone back to sleep. So by snoring his life away in luxury and comfort he never would have developed into the mighty Hercules.”

Now, this story of Hercules is a great example today, not only because it’s Greek mythology, but because it shows us that we need challenges if we want to grow.

Even a demigod, like Hercules, son of Zeus, the king of all Gods, and the son of the mortal woman Alcmene, but still a demigod, needs to face challenges in order to grow into the mighty Hercules, what do you think we need? We’re mere mortals. Of course we need challenges if we want to grow. Hey, we need to be willing to accept what life sets in front of us, and see those situations as challenges, so we might grow strong, and confident, and emotionally resilient. If we dare to aim up, and we need to if we want to grow as a person, then we need to be willing to struggle and persevere when life is demanding and challenging. In fact, these challenges are necessary for growth.

Do you think a person could reach his or her full potential without challenges? Impossible, we need those challenges. I say “challenges” instead of problems or disasters or hardships for a reason. That’s called cognitive reframing. Instead of looking at a situation as a disaster or problem, we can look at it from another angle and suddenly see it as a challenge, a challenge that might even be necessary for us to grow.

The Obstacle IS the Way, as Ryan Holiday wrote so famously. And it stems from Marcus Aurelius’ idea that what stands in the way becomes the way. It’s what we’ve said before, it’s where Viktor Frankl saw the very meaning of life. In seeing what life puts in front of us as our unique tasks. And that we are asked by life, and that we can only respond by being responsible.

Happiness and unhappiness consist in how we respond to events, the Stoics taught. “Make the best use of what is in your power, and take the rest as it happens.” Maybe we’d better turn this Epictetus quote the other way around: Take what happens, and make the best use of what is in your power. And suddenly, it becomes a continual process, like a circle.

Like a fridge that wants to stay at 5 degrees Celsius. When someone puts a hot cup of tea in the fridge, it needs to cool down. It takes the new situation, without complaining, and makes the best use of what’s in his power.

It’s like a circle. I want to be here. Oh, and now I’m here, so I need to correct to get back on track. For us, it’s the same in life, except that we’re aiming upwards. We don’t want to be at 5 degrees Celsius all the time, we want to get hotter. We want to move upwards, we’re aiming up.

So, that’s more like an upwards spiral. The fridge is a closed circle, but we’re spiraling upwards. We want to change for the better. We’re aiming up. And sure we struggle. So, it’s more like struggling upwards, but still it’s going upwards. Even if we fall, we continue. It’s zigzag. If we keep aiming up, and accepting the challenges and trying to make the best use of what’s in our power, we will get higher and higher.

If we move from A to B, and we’re at B now, nobody cares how we got from A to B. It was a constant struggle, zigzagging through the challenges. And that’s ok. It’s the norm. Because we’re all flawed. And we’re all struggling. That’s part of the game. Even Hercules was struggling. Just at another level, maybe. And with a bigger biceps.

Life is a process. This spiral will never end. It’s a continual process. And even if we believe we’ve successfully navigated through one obstacle, another will pop up quickly. Life will put another obstacle in our way. Constantly setting new challenges. And we learn as we go.

And here’s one more important point about this continual upwards spiral: We said that we need to aim up. And we need to be willing to face our challenges. Because moving upward and challenges only come as a pair. Many great teachers have taught us the same lesson: there is no pleasure without pain. No success without failure. If we’re willing to succeed, we need to be willing to accept failure as well. If you try to avoid failure, you will have to destroy the very possibility of success. And then you can’t aim up.

Life contains both; it brings great pain, and it brings great pleasure. Pain and pleasure are two sides of the same coin. If you exclude one, you have to exclude the other too. We cannot avoid the negative and only get the positive. The positive and the negative are together, we have to accept both. And sometimes, maybe, we cannot really tell whether something is positive or negative, whether something is good or bad, even if it seems pretty clear.

Let me tell you my favorite story. It’s called the Story of the Chinese Farmer.

So once upon a time there was a Chinese farmer. And he lost his horse, it ran away. So all his neighbors came by and told him, oh that’s too bad. And the farmer said, maybe.

The next day, the horse came back and brought seven wild horses with it. Now all the neighbors came by and told him, oh wow, that’s fantastic, isn’t it?. The farmer said, maybe.

The next day, the farmer’s son tried to tame one of the wild horses, and fell off the horse and broke his leg. Again, all the neighbors came by and told him, oh no, that’s terrible, isn’t it? The farmer said, maybe.

The next day, recruiters from the army came by looking for people for the army. And they rejected the farmer’s son because he had a broken leg. Now all the neighbors came by and said, well, isn’t that wonderful? And he said, maybe.

The whole nature is so complex that it’s really impossible to tell whether something is good or bad. Even if it seems so. It’s impossible to know the consequences of “misfortune.” And you will never know the consequences of “good fortune.”

That’s why the Stoics said that events themselves are neutral. It’s just a question of our perception. And what matters is what we do with the given circumstances. That we accept our response-ability. No matter what happens, whether it seems good or bad, we are asked by life. Now how do you respond?

Conclusion

Let’s wrap this up with where we started: Gaius Musonius Rufus. He was exiled to Gyros in the year 65 by the Emperor Nero. When Nero died three years later, Rufus returned to Rome and taught Stoic philosophy in his school. He became a famous figure in Rome under Emperor Vespasian. So when Vespasian banished all philosophers from Rome, he was allowed to remain. But not for long, in around 75, he was exiled again.

And where? You guessed it, Gyaros. This desolate island not far from here (Athens). After Vespasian’s death four years later, he returned to Rome once again and taught Stoicism. And from his remaining Fragments and Discourses, which are notes taken from two of his students, we know that one of his main message was this: Practice trumps theory. He asked his students:

Suppose there are two doctors. One talks brilliantly about the practice of medicine but has no experience in taking care of the sick. The other is not capable of speaking well but is experienced in treating his patients according to medical theory. Which one would you go to , if you are sick?

I would go to the doctor who is experienced in healing.

Practice trumps theory. And that’s what I’ve tried to help you with today. To put the Stoics’ basic ideas into practice.

First, we need to start with ourselves. Remember the arch of stones that crumbles if you’re not able to look after yourself properly. Start with yourself. We want to express our highest version moment to moment to moment. We take stock and see where we are now, and decide where we want to go.

First, say to yourself what you would be, then do what you have to do. We aim up. And we focus on what we control, that’s how we navigate, we accept our situation, where we are now, and make the best of what’s in our power. What can I do about this mess in my room? Or in my life?

As Epictetus told us before: “If you want anything good, get it from yourself.” And we don’t want to get dragged behind the cart, but we want to run alongside smoothly, and make the best of the journey. And that’s where our most precious ability comes in: our ability to choose how we want to respond to events. This is our response-ability.

You’re exiled. Now, how do you respond? The event, exile, does not matter. What matters is how you respond to the given situation.

Maybe you need to pause, and tell yourself: “Wait for me, little impression, let me put you to the test.” Bring some awareness into the situation, so you can actually choose your response instead of reacting out of your first impression.

And hey, this is not easy. And it’s not supposed to be easy, because we’re aiming up. And going up is always hard. Remember, even Hercules was struggling with his challenges. And these challenges were necessary for him to grow into the mighty Hercules. We cannot expect to jump from here to where we want to go. This will be a challenge.

Pain and pleasure are two sides of the same coin. They come together. We can’t have the positive without the negative. And sometimes, maybe, we don’t even know what’s good and what’s bad, even if it seems clear. Your horse ran away? Oh, that’s too bad. Or is it? Thank you for reading.

Jonas Salzgeber writes for a small army of remarkable people at NJlifehacks.com and is the author of The Little Book of Stoicism. His practical writing style helps people with the most important step: to put the Stoic wisdom from book page to action.

Discover more from Modern Stoicism

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This is a practical step by step of living a resilient life. The smoothness and simplicity of the grammar makes it consumable for even people outside the field of philosophy.

It was my pleasure reading through.please keep up the good work.

Thank you

I am facing a challenge…knowing now how to respond and not react has been amazing. I am accomplishing the tasks required by the challenge. I am mindful of cleaning up my room/life.

[…] ‘The Stoics in Exile’ […]

[…] Image from https://modernstoicism.com/on-taking-responsibility-the-stoics-in-exile-by-jonas-salzgeber/ […]