Several months back, I wrote a post derived partly from experiences as a middle-aged man going to the gym, and partly by reflections on Stoic philosophy and practice. Those reflections set out some of what Stoicism contributes to understanding the things that come up in the course of regular physical exercise. They also derive from my own application of – and mulling over – Stoicism as I’m in the course of my tri-weekly grind.

I had intended to write a set of follow-up pieces going further into this topic a bit sooner, but as many of you readers can relate, there are only so many hours to each day, and seemingly innumerable demands continuously eating up those blocks of time – usually more than they have been allotted. Not wanting to allow too many weeks and then months to slip by before authoring at least one sequel post, I set aside some time to add another three of those reflections here.

Making and Maintaining Time For Exercise

A commitment to exercise regularly is very easy to make. People do it all the time, especially as a New Years resolution, or after a doctor’s visit during which one’s physician stresses the need to lose weight, strengthen muscles, help one’s bones or joints, increase flexibility, or better one’s cardio-vascular system. Health clubs and gyms typically see a boom in membership in January, and many people who sign up use the facilities only a few times. Others don’t go at all. Some don’t cancel their memberships, but don’t use them either.

There are, of course, all sorts of alternatives to joining a gym. One can take a class, exercise on one’s own, or even get involved in pick-up games at community centers. There are meetups specifically for those who want to exercise in various ways, including just taking walks. Many workplaces have programs intended to get people moving and more active (in the American context, I write from, these are often tied to the health insurance offered by the company – the idea is that healthier employees result in lower insurance payouts). One can also just exercise on one’s own outside or in one’s own place – that was my preferred way, at earlier points in my life.

It is easy to make a choice to exercise, and even to elevate it to the status of a “commitment”. Following through on that is considerably harder. Physical exercise – at least until one has reached a point where this is no longer the case – is difficult, painful, tiring. It demands that one make a choice, or better put, renew the choice one has made, over and over again. That is what a commitment that one sticks with really looks like – a whole sequence of similar choices, maintaining at the least the direction that one started out in, if not necessarily the initial speed or attitude.

Maintaining commitment to exercise affords and opportunity – and also demands, in whatever degree we have it – the virtue that Stoics identified as courage or bravery (fortitudo in Latin, andreia in Greek). There are multiple modes of courage – what the Stoics called “parts” of that virtue – and some are more centrally involved in sticking with physical exercise one has committed oneself to. Perseverance (tharraleotes), which Arius Didymus tells us the Stoics defined as “knowledge ready to persist in what has been correctly decided”, and Industriousness (philoponia), which is “knowledge able to accomplish what is proposed, without being prevented by the toil” (Epitome of Stoic Ethics 5b2) are particularly relevant.

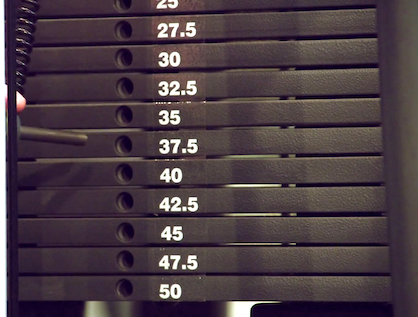

In working through just one of the fourteen weight-machine exercises that comprise my circuit workout, there are ample opportunities to choose not to follow through each time I go to the gym. And correspondingly, in order to keep the commitment to exercising my body fully, choices have to be made over and over again. It’s easy at the start of the first set. Depending on how I’m feeling and how much weight I’m using, it might be a good bit tougher near the end of the first set of repetitions. By the third set, if I’m using the right amount of weight, and not taking overly-long breaks between sets, the repetitions have become much more demanding. Each one towards the end requires an effort to push through pain and fatigue.

Sometimes I find myself tempted to round the number down. I notice my thoughts suggesting that it would be fine for me to do ten reps instead of twelve on the last set. Nobody else would know, since I’m on my own – fortunately, as an overweight near-50 year old, I enjoy near invisibility at the gym – and I’m not accountable to anyone else. Those thoughts suggest that since I’ve already done two whole sets, it would be all right to back off a bit on the final set. They arise less often than when I first resumed lifting a year and a half ago, but I still have to decide to push through to the end. In one sense, that’s bad, but in another – as I’ll discuss below – it’s not.

Choices and commitments not only have to be made at the gym. Before that, one has to actually make the time for exercise, and that requires choices and commitments as well. Busyness, fatigue, and occasional illness are the main factors that renders those difficult for me. For others, it might be a sort of laziness. Or it could be disorganization and distraction. Some may experience reluctance stemming from worries about others judging them on the basis of their present bodies. All of these challenges can be analyzed from the perspective of Stoic philosophy, revealing that they involve varieties of desires and fears, as well as associated assumptions, judgements, and typically developed habits.

As packed as my work schedule is between teaching classes, meeting with clients, engaging in consulting work, shooting videos and creating other content, varied duties with the Modern Stoicism organization and the Stoic Fellowship, among other things, I would sometimes find myself moving my scheduled workout around on my Google calendar to later times or to the next day. As work tasks took longer than planned, and time ran out, I inevitably skipped workouts. With old pets who occasionally require considerable care, children who visit from time to time, and a wife I chose a life with, I also prioritized family time over workout time. Over the five weeks of my kids’ summer visitation, in order to maximize our time together, I cut back considerably on both work and on workouts.

From a Stoic perspective, what we do or don’t make time for, particularly in relation to other things, reflects what Epictetus would call the price we actually place upon those things, on what we take to be goods or values, evils or disvalues, and the relative rankings of those in relation to each other. These valuations or prioritizations have both cognitive and affective dimensions. They reflect what we do – and have done – with what he calls our rational faculty and our faculty of choice (prohairesis, also sometimes translated as “moral purpose”).

There’s a bit of good news and bad news involved in that. The bad news is that since what we choose and do – as with anyone else – flows naturally from the established structures of thought and volition, largely determined by established habits and assumptions, unless we choose to use those two faculties to examine and modify themselves, we will go on along those same lines. Skipping scheduled workouts will keep on happening, as other things assume higher priority when push comes to shove.

The good news, of course, is that we can willingly choose to rethink how we value and prioritize. We can take cognizance of and modify our habits. In the case of physical exercise, we can remind ourselves of its value and necessity. If we want to take care of the bodies we have been given – which is the rational and practically wise thing to do – then we do have to make time for regular exercise. And that means then that once we have made that time, we have to follow through and maintain that time by not allowing other matters to keep us from using it in the way and manner we decided.

Returning To An Abandoned Routine

Interesting and illuminating analogies can be drawn between physical conditioning, which has some value, and the training of the soul, which from a Stoic perspective possesses a much greater value. In order for any lasting changes to be made, a person must deliberately and repeatedly engage in exercises, choosing over and over again to build and develop new capacities. Those processes of self-improvement, of building what is good and strong in us, and rooting out what is bad and weak, work best when they are continuous, but that is rarely the way things work out.

When it comes to regular exercise not only might one end up breaking one’s scheduled pattern, failing to make or maintain the needed time, abandoning one’s routine for other matters valued more highly. Illness or fatigue can also create obstacles. In fact, those can present hindrances even more for working out than they do for daily reading and study of Stoic texts, or regularly engaging in Stoic exercises. It can be difficult to maintain mental focus when sick or overtired, which may make a session of reading or practical exercise less effective. But it can prove harmful to the body to exercise while ill or sleep-deprived.

One of the adages I inevitably tell my students when I teach Ethics classes or material, is that studying practical philosophy isn’t just supposed to provide us with the guidelines for making the right decisions every time. It is also there to help us, after we’ve made the wrong ones, to figure out just how much we’ve messed up, and what we can do to get ourselves back on track. Stoic ethics is no exception in this respect. When you read through the works we possess by Epictetus, Seneca, and Marcus Aurelius, you will find many passages dealing precisely with that general issue, often focused on particular lapses, mistakes, and deviations.

If getting one’s body back into shape – or perhaps for some, getting it into proper condition for the first time – is something that one decided to be valuable, and still thinks it to be valuable, but one hasn’t managed to stick with regular exercise, then as with any other matter where one notices a contradiction or conflict between the things one thinks, says, values, chooses, and does, then some self-examination is called for. Simply making excuses for why one neglected exercise, or pretending one didn’t have a lapse, or wishfully thinking to oneself that one is going to simply pick right back up and get right back into exercise – these aren’t responses that are likely to be effective.

But once a person acquires some understanding of why what they seem to have resolved to do doesn’t actually happen – when they are the person who gets to determine it – then using that insight, they can change what happens going forward. In my own case, realizing that despite the value I seemingly set upon bodily health – and my realization that regular exercise is a necessary means to that health – I wasn’t getting to the gym regularly enough prompted me to take a look at my habits, assumptions, emotions, and choices involving work.

I’m still practically speaking a workaholic, but by engaging in self-examination and thinking matters through, I was able to break the habit of allowing work obligations to displace scheduled workouts from my calendar, and thereby my day. I saw the larger pattern comprised of many small “just this time” incidents, and then was able to gradually establish a new pattern. Deliberately reminding myself of my realization and resolve that, if I want this body to serve me well past middle age (fate willing of course), I had to keep those workout appointments I’d made by hitting the gym – each occasion that I would have allowed work to spill over into my workout times – that allowed me to get back on track.

A nasty flu bug hit here in the Midwest earlier this year – one that took weeks for most people to get over – and that put my workouts on hold as well. Skipping workouts due to illness is different than not persevering in making time, because as noted above, it may indeed be prudent not to exercise while ill. But what is the same in both cases for physical exercise – and for Stoic practices more generally – is the need to get oneself back on track when we have temporarily put them on hold.

This is where advice from classical Stoic philosophers can be helpful in providing perspective. Without making excuses for ourselves, we can realize that in our failure to follow through and keep commitments to ourselves to exercise, we are no different than any other person who has made a similar mistake. We can forgive ourselves the lapses without forgetting the need to change what within is led to those lapses. As classic Stoic philosophers point out, instead of getting upset with someone for a moral failing, it is more productive to show a person where they went wrong and then leave it up to them what they decide to do with that information. In the case of ourselves, we are that very person, and feeling guilty or angry with ourselves is less likely to get us back into the gym than allowing ourselves to make a new start.

After an absence from the gym, one really does need to make a new start. You can’t really make up for the workouts you missed by assigning yet more exercise to your body. That past time is gone, and that potential exercise that you might have done exists nowhere but in your imagination. All you do have is the present set of real moments and the indeterminate future stretching out in front of you. This is where the Stoic theme of “dealing with appearances” (phantasiai) assumes its importance. That imagination of where you had hoped to be, if you had stuck with the workouts that you missed – that’s an appearance, and one that you can examine and reject, when you encounter it. The sensations of your body as you resume your exercise, whether you feel strong or weak, doing well with an exercise or struggling with it, the pain and fatigue – all of those are appearances as well. The measures of the weights, the repetitions and sets, the time spent doing cardio or in a class – those quantities are all appearances.

We draw a host of judgements from those appearances, often with emotional correlates, all of which we can examine and even rework from a Stoic perspective. When I have gone back for a workout after missing more than a week, I have learned to prime myself to find out in the interaction between my body and the weights machines, what my current capacities really are and to carry out my workout in accordance with those. I do the same with the cardio machines (treadmill, elliptical, rowing, etc.). Invariably, I discover I have lost some ground, which makes good sense, since that’s the way bodies work. If you don’t exercise muscles, they get weaker. If you don’t do cardio of some sort, your endurance lessens. Trying to do the workout that you think you ought to be able to do, ignoring the time spent not exercising – or even trying to compensate for it – is making a bad or unreasonable use of all of those appearances.

A better use is to start up again where you find yourself. So you have to do less weight on all or most of the exercises in a weights circuit. Is that something bad for you – or something bad about you? Not at all. When I’ve been too invested in those numbers, and feeling bad about not being able to lift as much as before, I’ve found it useful to remember one of Epictetus’ short analyses of mistaken inferences.

“I am richer than you are, therefore I am superior to you”; or “I am more eloquent than you are, therefore I am superior to you”. The following conclusions are better: “I am richer than you are, therefore my property is superior to yours”; or “I am more eloquent than you are, therefore my elocution is superior to yours”. But you are neither property nor elocution

Enchiridion, ch. 44

The context would suggest that this reminder applies to cases where we are likely to mistakenly assume our own superiority over other people, or where we need to deal with other people’s assertion of superiority over ourselves or yet others. But it can equally apply to our own assessment of ourselves. If a month earlier, I could easily lift ten pounds more weight on a pulldown machine, and now find myself struggling to get through my three sets with the reduced weight, that doesn’t mean that I have become less of a person. It does mean that I can’t exercise with as much weight. How much weight one can use and the moral status of oneself as a person are two totally different things. If I do want to be able to lift more weight, then I need to exercise. If I want to become a better person, well there are Stoic exercises and insights for that as well!

Some Final Thoughts Keeping The Body In Perspective

Applying Epictetus’ passage along those lines, distinguishing one’s physical capacity from one’s moral condition and development, might then raise a question about the body and exercise from a Stoic perspective that I discussed in the previous post in this series. Strictly speaking, the body and its attributes – like health, strength, or endurance – is an indifferent. We are no more our bodies, their appearances, or their capacity for exercise than we are our wealth or our ability to speak well, right? Epictetus goes so far at one point to say that what a person really consists in, is prohairesis. So why place such a focus on bodily exercise as something important from a Stoic perspective?

I’ll devote additional discussion to this entirely legitimate question in a later post in this series. For now, to bring this to a close, I’ll just point out two things worth mulling over.

One of them is the frequency of Stoics drawing analogies between physical exercise, condition, and even the use of the body, on the one hand, and the understanding, development, and use of what is more at the core of who we are. This is what the Stoics called the ruling faculty (to hegemonikon, which, arguably, turns out to be the same as the rational faculty and the faculty of choice, at least in Epictetus). Bodies don’t start out automatically in good condition, and require the right kinds of exercise in order to improve in health, strength and other attributes. And this goes even more for our souls, which require considerably more attentiveness and work in order for us to more fully realize the potentials of our rational nature.

One of those analogies that I find particularly helpful, as I try to stick with incorporating and continuing bodily exercise comes from Epictetus:

How long will you wait to think yourself worthy of the best things?. . . You have received the philosophical principles which you ought to accept, and you have accepted them. You are no longer a child, but a full-grown adult. If you are now neglectful and easy-going, and always making one delay after another. . . . then without realizing it you will make no progress . . . . Make up your mind, therefore, before it is too late, that the fitting thing for you to do is to live as a mature person who is making progress. . . .[R]emember that now is the contest, and here before you are the Olympic games, and that it is impossible to delay any longer, and that it depends on a single day and a single action, whether progress is to be lost or to be saved.

Enchiridion, ch. 51

We can apply this advice that emphasizes the importance of each choice at each present moment just as readily to physical exercise as we can to applying Stoic philosophy and practices. Each repetition we force our body’s muscles to carry out (particularly the difficult ones at the end!), each minute one keeps pumping away -sweat-soaked and fatigued – on the elliptical is that single action. And whatever bodily exercise one does not only can be, but calls to be incorporated in a broader Stoic perspective.

One of Seneca’s discussions casts light on this. In a letter presenting Stoic arguments about the equality of virtue (an interesting topic, which I’ll examine more fully in another post), he looks at a contrast some would make between the matters in which virtue is exercised:

“What then,” you say; “is there no difference between joy and unyielding endurance of pain?” None at all, as regards the virtues themselves; very great, however, in the circumstances in which either of these two virtues is displayed. In the one case, there is a natural relaxation and loosening of the soul; in the other there is an unnatural pain. Hence these circumstances, between which a great distinction can be drawn, belong to the category of indifferent things, but the virtue shown in each case is equal. Virtue is not changed by the matter with which it deals; if the matter is hard and stubborn, it does not make the virtue worse; if pleasant and joyous, it does not make it better. Therefore, virtue necessarily remains equal.

Letter 66

To be sure, the examples he discusses in that letter (and the one following) are more extreme than just making through one’s workout at the gym – include bravely enduring torture, showing fortitude in illness, or dealing with exile – but the same logic applies to exercise. It offers us the opportunity to develop and deploy the virtues in engaging with goods that “manifest only in adversity”. Seneca even clarifies this matter in relation to the Stoic conception of what is “in accordance with nature”.

The two kinds of goods which are of a higher order are different; the primary are according to nature, – such as deriving joy from the dutiful behaviour of one’s children and from the well-being of one’s country. The secondary are contrary to nature, – such as fortitude in resisting torture or in enduring thirst when illness makes the vitals feverish. “What then,” you say; “can anything that is contrary to nature be a good?” Of course not; but that in which this good takes its rise is sometimes contrary to nature. For being wounded, wasting away over a fire, being afflicted with bad health, – such things are contrary to nature; but it is in accordance with nature for a man to preserve an indomitable soul amid such distresses. To explain my thought briefly, the material with which a good is concerned is sometimes contrary to nature, but a good itself never is contrary, since no good is without reason, and reason is in accordance with nature.

Letter 66

I’ll leave off here with a brief interpretative suggestion. In one sense, physical exercise of the sort that one typically does at a gym – deliberately pushing oneself to limits of strength, endurance, flexibility, or other bodily qualities – are indeed unnatural. The pain or fatigue one endures is hopefully not anywhere near as intense as being tortured on a rack, of course, and the circumstances are very different, since one chooses to work out. In another sense, physical exercise is something in accordance with nature, not only because it enables us to develop our bodily capacities and to maintain our bodies in a state of health, but also because when conducted well, the “use” or “dealing with” the indifferents that our bodies are can provide a locus for exercising the virtues.

Gregory Sadler is the Editor of the Stoicism Today blog. He is also the president and founder of ReasonIO, a company established to put philosophy into practice, providing tutorial, coaching, and philosophical counseling services, and producing educational resources. He teaches at the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design. He has created over 100 videos on Stoic philosophy, regularly speaks and provides workshops on Stoicism, and is currently working on several book projects.

Discover more from Modern Stoicism

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Wow, a great many words. I have a suggestion: Forget the machines and hiding in the white noise of the gym. Undergo serious free weight training, take center stage in the gym, show all that you are committed to muscle maintenance the correct way, even if you are lifting 20lbs. Not only will be it an act of courageous pursuit on your part it will present a dynamic illustration that the free weight section of the gym is not only for the Arnold’s, and you don’t have to wear pajama pants and wife-beaters to lift weights. I think this would be liberating for all involved. You might be so invigorated by the public demonstration, it may give you a new interest, a new reason to go to the gym. Fun.

Nah. I’ve done the free-weight thing plenty back when I was younger. I’ve got something that works well for me, and not looking for one-size fits all advice.

I lifted my first weights well over 64 years ago. I vividly recall the first clean and jerk. My brother gave me my first set of weights. He was almost 10 years older than I was. Whereas nothing seemed to come naturally or easy to me, he appeared to me to make everything look easy. My introduction to Stoicism came a number of years ago with my reading of an article written by Donald Robertson. That short read would be one of the major life changing events in my life. It’s so interesting how an event such as weight lifting would have such impact on the rest of my life.

Namaste