The 2021 edition of Stoicon, the online international conference for people interested in Stoic philosophy, has concluded. I presented a somewhat provocative talk bearing the title of this article, just to stir the pot a bit. You see, Stoics (both ancient and modern) more than occasionally have a tendency to slide into dogmatism. And what better antidote for dogmatism than a bit of skepticism?

In particular, I wanted to stimulate some reflection on a crucial debate that unfolded between ancient Stoics and Skeptics, concerning the nature of knowledge. We are talking epistemology, baby! As I will argue in this essay, a good understanding of what constitutes knowledge is not just a matter of interest to professional philosophers, it actually has practical consequences for the way we think and act. And, in this regard at least, the Skeptics had a better argument than the Stoics. Let’s take a look.

First off, what do we mean by “knowledge”? Although there are interesting debates about this in modern philosophy, for the purposes of this discussion I’m going to stick with the time tested definition we owe to Plato (in Meno 98 and Theaetetus 201): knowledge is Justified True Belief, or JTB.

Meaning what? Well, if I claim to know something, according to Plato, three conditions must be met. Most obviously, I have to believe it. It would be weird, for instance, for me to say that I know that my friend Phil lives on Long Island, and yet not actually believe it.

Second, I have to be able, if asked, to justify my belief. Here things get a bit more complicated. How do I know that Phil lives on Long Island? Well, I’ve seen his house, for one. But do I really know that that’s his house? It could be that of a neighbor who temporarily loaned it to him. After all, I haven’t seen Phil’s deed of ownership or rental contract. Nor have I verified that he lives there on a regular basis, since I myself live in Brooklyn, and only rarely go to Long Island.

Things get far worse for less mundane claims to knowledge. If asked, for instance, I might say that I “know” that electrons are subatomic entities characterized by a dual particle-wave nature. But do I really know this? I can’t actually justify this particular belief, other than by referring you to my colleagues in the Physics Department. Or to the proper Wikipedia page. According to Plato, therefore, I don’t really know what electrons are. Indeed, it turns out that according to the JBT criterion, most of us know only a fraction of the things we think we know. Humbling.

But that’s not the problem the Skeptics and the Stoics were going about during the Hellenistic period. That problem concerned the third component of JTB: truth. How do we establish the truth of a proposition? Some propositions may be true by definition. For instance, 2+2=4. But what about propositions concerning the world? To assess that sort of propositions we typically use two tools: perception and reason. (Anything else, like intuition, or transcendental knowledge, either reduces to a form of perception + reason or it doesn’t provide us with knowledge at all.)

The problem is that we know that both our senses, through which we perceive things, and our reasoning abilities can go wrong. So how do we ever know for sure that, well, we know something? Let’s start with the Stoic take. A good way to understand the Stoic conception of knowledge is a summary of it provided by Cicero, where he tells us of a metaphor employed by Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism:

Zeno professed to illustrate [his notion of knowledge] by a piece of action; for when he stretched out his fingers, and showed the palm of his hand, ‘Perception,’ said he, ‘is a thing like this.’ Then, when he had a little closed his fingers, ‘Assent is like this.’ Afterwards, when he had completely closed his hand, and held forth his fist, that, he said, was comprehension. From which simile he also gave that state a name which it had not before, and called it katalepsis. But when he brought his left hand against his right, and with it took a firm and tight hold of his fist, knowledge, he said, was of that character; and that was what none but a wise person possessed. (Cicero, Academica II.XLVII)

I have written in detail about this before, but the basic idea is that there are several, increasing degrees of understanding: Perception > Assent > Comprehension/Katalepsis > Knowledge.

As I mentioned above, our knowledge of things begins with our sensorial perceptions. Both the Stoics and the Skeptics, in this regard, were empiricists (so were the Epicureans and the Peripatetics, incidentally, though not the Platonists). In most cases we stop at the second stage: we perceive something and more or less automatically give “assent” to it and call it a day.

For instance, I may see (perception) what looks like a pomegranate on the kitchen table, and assent (consciously or unconsciously, doesn’t matter) to the proposition: “there is a pomegranate on the kitchen table.” This is what the Stoics call an impression: a cognitive or non-cognitive assent to a perception. (I’ll stick with pomegranates for a while, the reason will become clear near the end of this article.)

But this isn’t really knowledge, according to both Skeptics and Stoics. We get a bit closer, as far as the latter are concerned, if we move from standard impressions to kataleptic ones. Perhaps the best way to understand what the Stoics mean by katalepsis is to use an example from Epictetus (Discourses, I.28.1-5).

Suppose it is now day where you live. Now go outside and try really hard to convince yourself that it’s the middle of the night. You can’t. That’s because you are having what appears to you to be a kataleptic, i.e., undeniable, impression: it is day. Katalepsis, for the Stoics, is a criterion of truth. If you are in the presence of a kataleptic impression that’s a sure indication that you are grasping a truth. In this case, that it is day, not night.

But hold on a minute. What if I am hallucinating? Or maybe I’m dreaming. Or perhaps it is, in fact, night, but a powerful explosion makes it seem like it is day. In other words, regardless of how strong the kataleptic impression feels, it could still not be true.

When that happens, the Stoics say, it is because the impression was not really kataleptic. That is why Zeno added one more step to the sequence: “knowledge, he said, was of that character; and that was what none but a wise person possessed.” Only the sage, the perfect Stoic, can actually tell whether an apparently kataleptic impression is or is not, in fact, kataleptic. Therefore, only the sage can arrive at knowledge. Why? Because what defines the sage is precisely the ability to always arrive at correct judgments, since his faculty of reasoning have been developed to perfection.

Yeah, right, responds the Skeptic. Before we examine the Skeptic position, though, we need to distinguish between the two major Hellenistic schools of Skepticism, only one of which is pertinent to our concerns here: Pyrrhonism, and New or Academic Skepticism.

Pyrrhonism, so named after the founder of the school, Pyrrho of Elis (in modern western Greece) thought that we should not hold onto any opinion (“dogma,” in ancient Greek) about non-evident matters. (Let us set aside for now exactly what does and does not count as a non-evident matter.) We accomplish this by practicing epoché, that is, suspension of judgment. And we do it because the goal of life, for the Pyrrhonist, is the same as for the Epicurean: ataraxia, a state of equanimity and mental tranquility, which is imperiled by holding to opinions.

Let’s put some flash onto this, before we turn to Academic Skepticism. Many of us have strong opinions about all sorts of “non-evident” matters, including political and religious ones. For Pyrrho and his followers, this is a mistake, because there is no certain knowledge that can possibly be achieved on these issues. Our insistence on not suspending judgment about politics or religion, then, is the cause of our anger, frustration, and so forth, which keeps us from ataraxia. I think Pyrrho had a point. But the Stoics had a good response to this sort of Skepticism: if we truly engage in epoché, on what basis are we going to decide whether and how to act, in any given circumstance? If we stay away from judgments, how do we actually live our lives? (In Outlines of Pyrrhonism Sextus Empiricus responds that the Skeptics do have criteria for action, but that they do not involve beliefs, and at any rate do not apply to non evident matters. If you are interested, compare his I.11, I.12, and I.13)

Enter Academic Skepticism, so named because that group of Skeptics took over Plato’s Academy between 266 BCE and 90 BCE, give or take. The New Skeptics held that human beings cannot achieve certain knowledge, because — as we saw above — our two means of acquiring knowledge, our senses and our reasoning abilities, are fallible. New Skeptics thought of themselves as going back to Socrates, who famously was the wisest man in Greece, according to the Oracle at Delphi, precisely because he was aware that he didn’t know anything.

The good news, though, is that action is possible because we can assess the probability of a statement being true. If so, we can make our decisions based on such estimates of probabilities. Indeed, Cicero, an exponent of the New Academy, coined the term probabilis, from which we get the English probability, when he needed to translate the original Greek, pithanon, a word meaning “persuasive,” or “plausible.” Incidentally, the goal of life, for the New Skeptics, was not ataraxia, but rather a practical life of virtue, which is to say, the same goal of the Stoics.

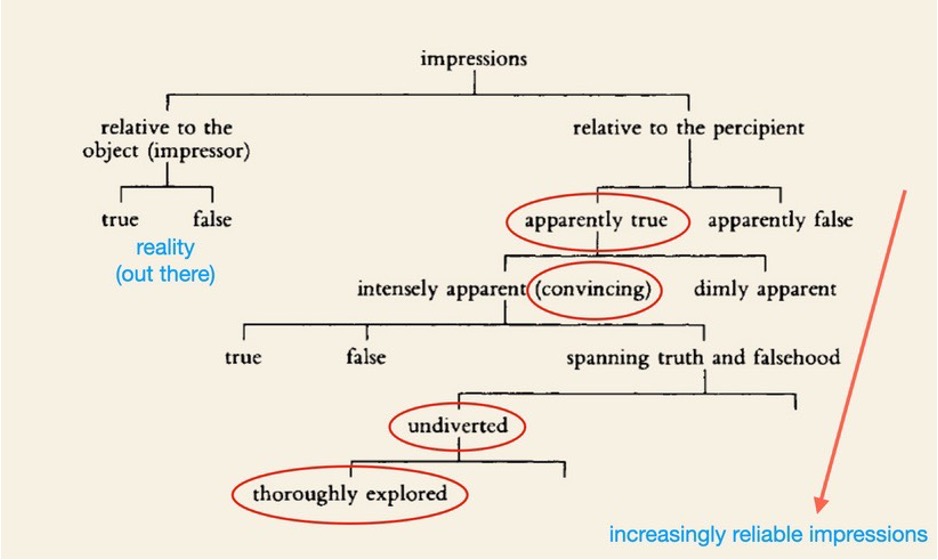

The New Skeptics too, like the Stoics, recognized a sequence of increasingly more reliable impressions, which is summarized in this figure, modified from Long and Sedley’s The Hellenistic Philosophers.

Starting from the upper tier, we see (left) that the New Skeptics assumed the existence of an external world, which is the source of our impressions. This is not argued for, it is simply a reasonable axiom of their epistemology. All the action is therefore confined to the right side of the diagram, which pertains to the percipient of impressions. The lowest level of impression (high in the diagram) is merely “apparently true.” The next level is “intensely apparently true” or “convincing.” Further down in the figure we find the two highest levels of impressions: “undiverted” and “thoroughly explored.” Let’s take a closer look at the last two categories.

Starting from the upper tier, we see (left) that the New Skeptics assumed the existence of an external world, which is the source of our impressions. This is not argued for, it is simply a reasonable axiom of their epistemology. All the action is therefore confined to the right side of the diagram, which pertains to the percipient of impressions. The lowest level of impression (high in the diagram) is merely “apparently true.” The next level is “intensely apparently true” or “convincing.” Further down in the figure we find the two highest levels of impressions: “undiverted” and “thoroughly explored.” Let’s take a closer look at the last two categories.

An impression is “undiverted” when it coheres with all the other impressions we have. When an undiverted impression is “thoroughly explored,” i.e., it is subject to a meticulous examination to see if it really stands up to scrutiny, it becomes even more reliable. But, crucially, never certain, unlike Stoic true katalepsis.

Let’s go back to the pomegranate allegedly sitting on my kitchen counter. A first glance at it generates an apparently true impression. The impression becomes intensely apparent once I start paying attention and look at the pomegranate a little more carefully. Yup, it does look like the real thing! But is it? Let’s move to the next level of confidence: my impression becomes “undiverted” if not only I see what looks like a pomegranate, but I can also smell it, and perhaps taste it. Not convinced yet? Fine, let’s undertake a thorough exploration of the thing, perhaps including a DNA analysis and a quick consultation with a botanist, both of which steps will confirm that I am indeed in the presence of a fruit belonging to the species Punica granatum, a deciduous shrub in the family Lythraceae native of the Mediterranean region (but introduced in Spanish America in 1769).

So what is the difference between the Stoic and the New Skeptic approach here? The latter has no sure criterion of truth, no equivalent to katalepsis and sages because, the New Skeptics maintained, there is no such thing as katalepsis, and consequently no such thing as sages. More importantly, there is no such thing as certain knowledge, only probabilities.

Who was right, the Stoics or the New Skeptics? In this case my vote is decidedly for the latter. And most modern philosophers agree. In particular, the New Skeptics anticipated three dominant currents in modern epistemology:

- Probabilism, which holds that in the absence of certainty, plausibility or truth-likeness is the best criterion;

- Fallibilism, which holds that no belief can have justification which guarantees the truth of the belief;

- and Coherentism, which holds that epistemic justification is a property of a belief only if that belief is a member of a coherent set.

Okay, you might justifiably say, but why do we care? There are five direct consequences of the debate between Stoics and Skeptics on the nature of knowledge.

First, one lesson is that we should not venerate the ancient Stoics. They were human beings, not prophets. Too many modern Stoics seem to think otherwise and treat Stoicism almost as a religion. Despite the fact that some of the ancient Stoics themselves, for instance Seneca (in Letter XXXIII.11) warned against regarding, as he put it, our forerunners as masters, rather than just teachers. Realizing that the Stoics did get certain things wrong, as in the case of this debate, is a healthy tonic against treating Stoicism as a rigid doctrine rather than a dynamic philosophy.

Second, sages don’t exist. Seneca himself (Letter XLII.1) says that they are as rare as the phoenix, the mythological bird that rises from its ashes every five hundred years. We may take the extra step and agree with the New Skeptics that human beings can never be sages, period. Which has healthy consequences, particularly as it nudges toward practicing humility.

Third, the Stoic sage is supposed to be the only human being capable of true knowledge. Virtue is a type of knowledge. So the sage is the only one who is truly virtuous. The rest of us are vicious, and in fact, according to ancient Stoicism, equally vicious. Some people, both in ancient times and in modern ones (including yours truly!), have twisted themselves into logical pretzels to defend this indefensible Stoic notion. Let us just abandon it and agree with not just the Skeptics, but pretty much everyone else, that virtue comes in degrees, like any other kind of knowledge. Because by its nature, knowledge is probabilistic, not all or nothing.

Fourth, contra the ancient Stoics, knowledge is not necessary in order to engage in action. Plausibility is all we need. Again in this sense the New Skeptics were far more in line with modern epistemology than the Stoics. In particular, their approach can easily be recast as what today is known as Bayesianism, a current in epistemology according to which we can use the famous Bayes theorem to update our assessment of the likelihood of a proposition in proportion to new evidence coming in pro or against that proposition.

Fifth, assent — that crucial Stoic concept on which Epictetus constantly insists — should be given only provisionally and with caution. Just like a good Skeptic would.

And this is the time where I’m finally going to explain all the references to pomegranates. Diogenes Laertius, in the Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, book VII, tells the story of Sphaerus of Borysthenes (a location on the Black Sea). Sphaerus was a Stoic philosopher and student of both Zeno and Cleanthes, the first and second heads of the Stoa. He moved to Sparta to teach and to advice king Cleomenes III.

Diogenes says that one day the king tested Sphaerus’ talk of kataleptic impressions by presenting him with a plate of delicious looking pomegranates. When Sphaerus picked one up to eat it, he discovered that they were made of wax. The king then pointed out that Sphaerus’ Stoic theories did not seem to hold up too well in actual practice:

“‘You have given your assent to a presentation which is false.’ But Sphaerus was ready with a neat answer. ‘I assented not to the proposition that they are pomegranates, but to another, that there are good grounds for thinking them to be pomegranates. Certainty of presentation and reasonable probability are two totally different things.’” (DL, VII.177)

Indeed they are. But in saying so, Sphaerus conceded the point to the Skeptics.

Massimo Pigliucci is an author, blogger, podcaster, as well as the K.D. Irani Professor of Philosophy at the City College of New York. His academic work is in evolutionary biology, philosophy of science, the nature of pseudoscience, and practical philosophy. His books include How to Be a Stoic: Using Ancient Philosophy to Live a Modern Life and Nonsense on Stilts: How to Tell Science from Bunk . His most recent book is Think like a Stoic: Ancient Wisdom for Today’s World (Teaching Company/Audible). More by Massimo at Philosophy As A Way Of Life.

Discover more from Modern Stoicism

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.